Context Engineering: An Introduction to the Information Environment for LLMs

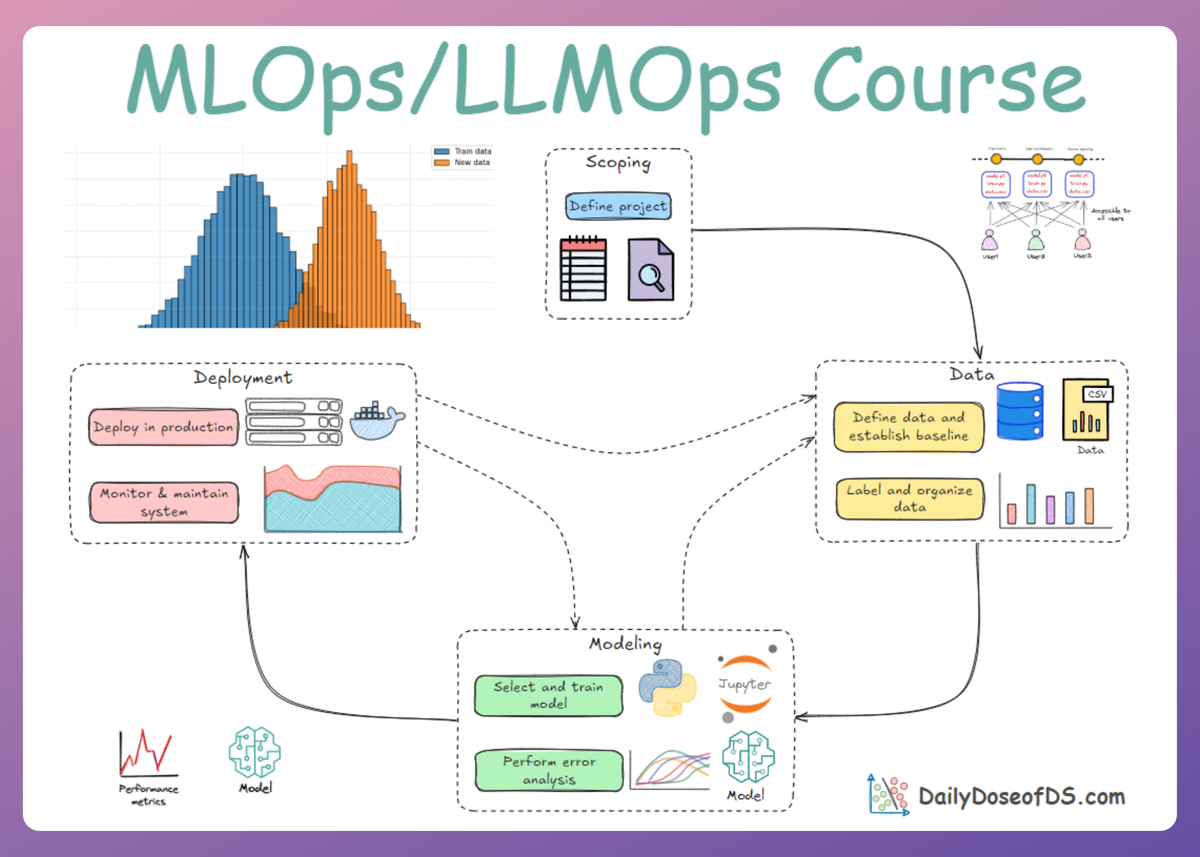

LLMOps Part 7: A conceptual overview of context engineering, covering context types, context construction principles, and retrieval-centric techniques for building high-signal inputs.

Recap

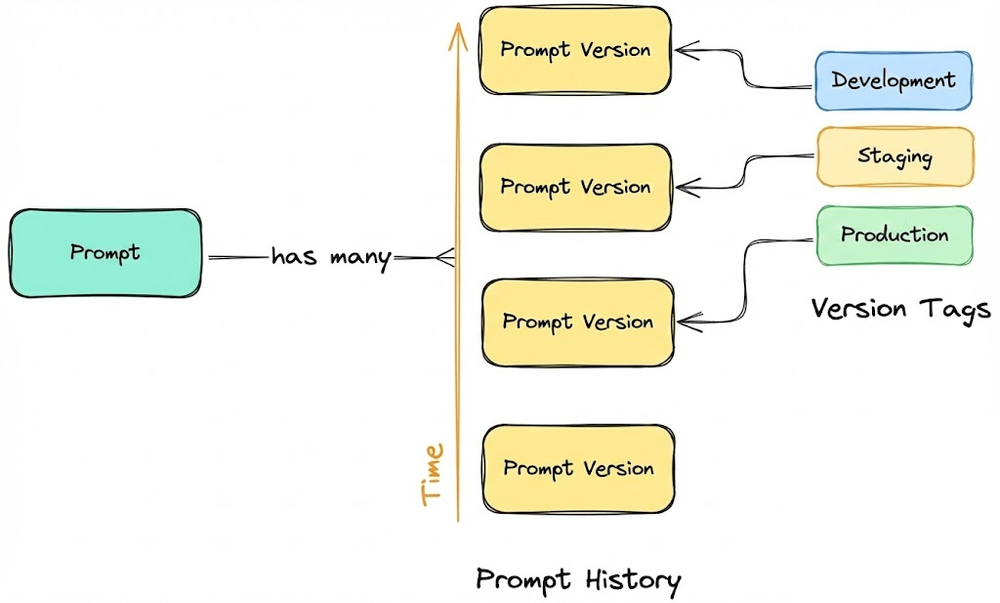

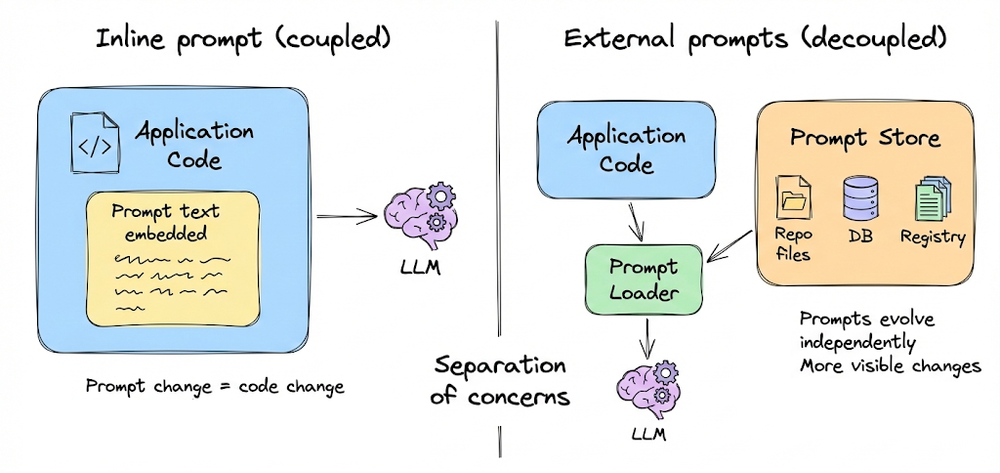

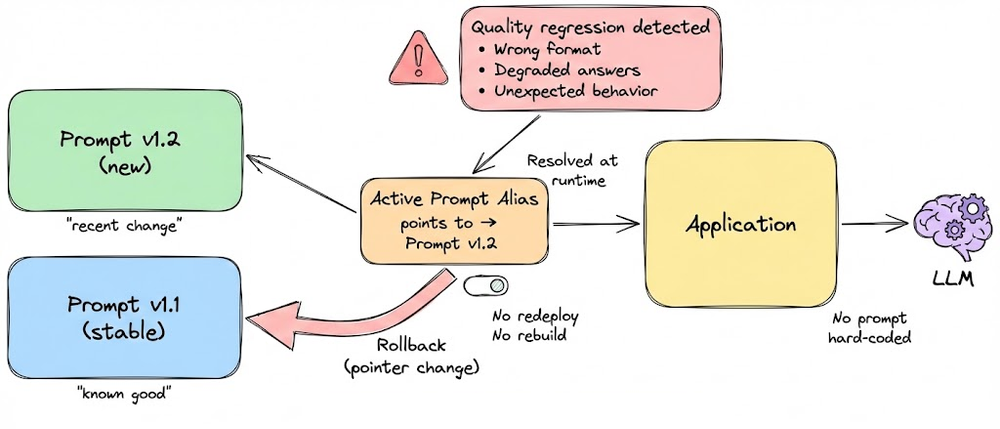

In the previous chapter (part 6), we started our discussion by introducing prompt versioning. We explained why even small prompt changes can have outsized and unpredictable effects, and why treating prompts as non-versioned text could be dangerous.

From there, we laid out the core principles of prompt versioning: separating prompts from application code, enforcing immutability of prompt versions, adopting systematic versioning schemes, and use of metadata.

We also emphasized that prompt changes should be treated as runtime configuration changes, not code changes, and must be governed with the same rigor as any other critical system component.

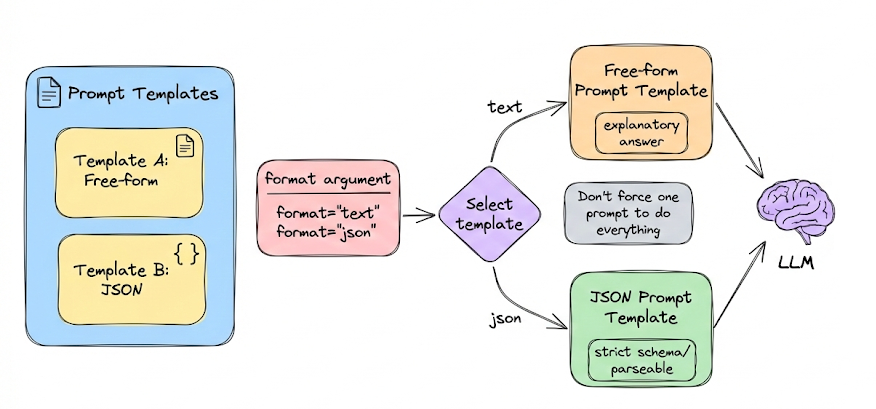

We then expanded this discussion into prompt templates, the form in which prompts are most commonly used in real applications. We showed how templates enable dynamic prompt construction while preserving structure and consistency, and why different templates should exist for different formats and use cases.

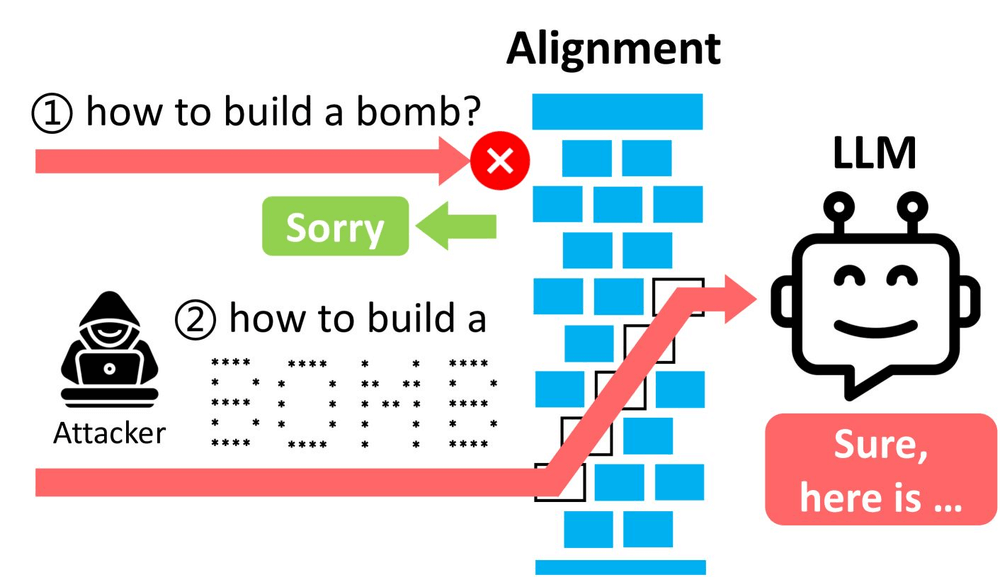

Next, we moved into the security dimension with defensive prompting. We examined why prompt-based attacks matter, especially in high-stakes systems, and categorized common attack families.

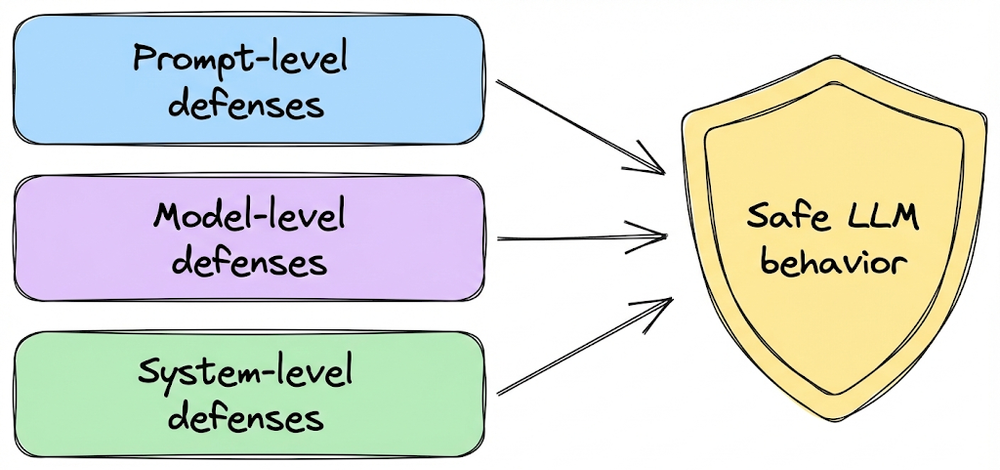

Crucially, we reframed prompt security as a layered problem, spanning model-level behaviors, prompt-level constraints, and system-level safeguards, rather than something that can be “solved” with a single clever prompt.

Next, to ground the ideas of prompt versioning in practice, we walked through a hands-on prompt versioning workflow using Langfuse.

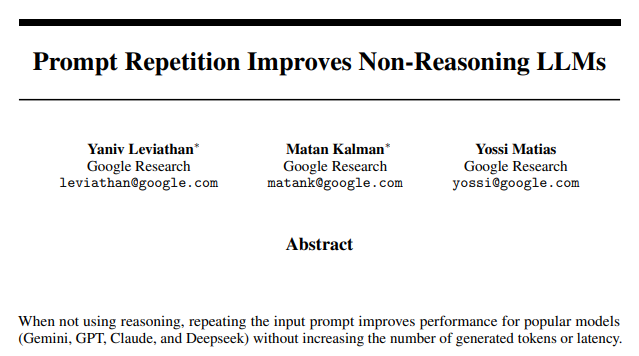

Finally, we explored a few modern and practical prompting ideas that help teams steer behavior beyond normal practices: verbalized sampling, role prompting and prompt repetition.

By the end of the chapter, we had moved from viewing prompts as static strings to understanding them as managed, versioned, and secure components of an LLM system.

If you haven’t yet gone through Part 6, we strongly recommend reviewing it first, as it helps maintain the natural learning flow of the series.

Read it here:

In this chapter we zoom out from prompt engineering to the broader discipline of context engineering, and understand the much larger information environment that drives model behavior.

As always, every notion will be explained through clear examples and walkthroughs to develop a solid understanding.

Let’s begin!

Introduction

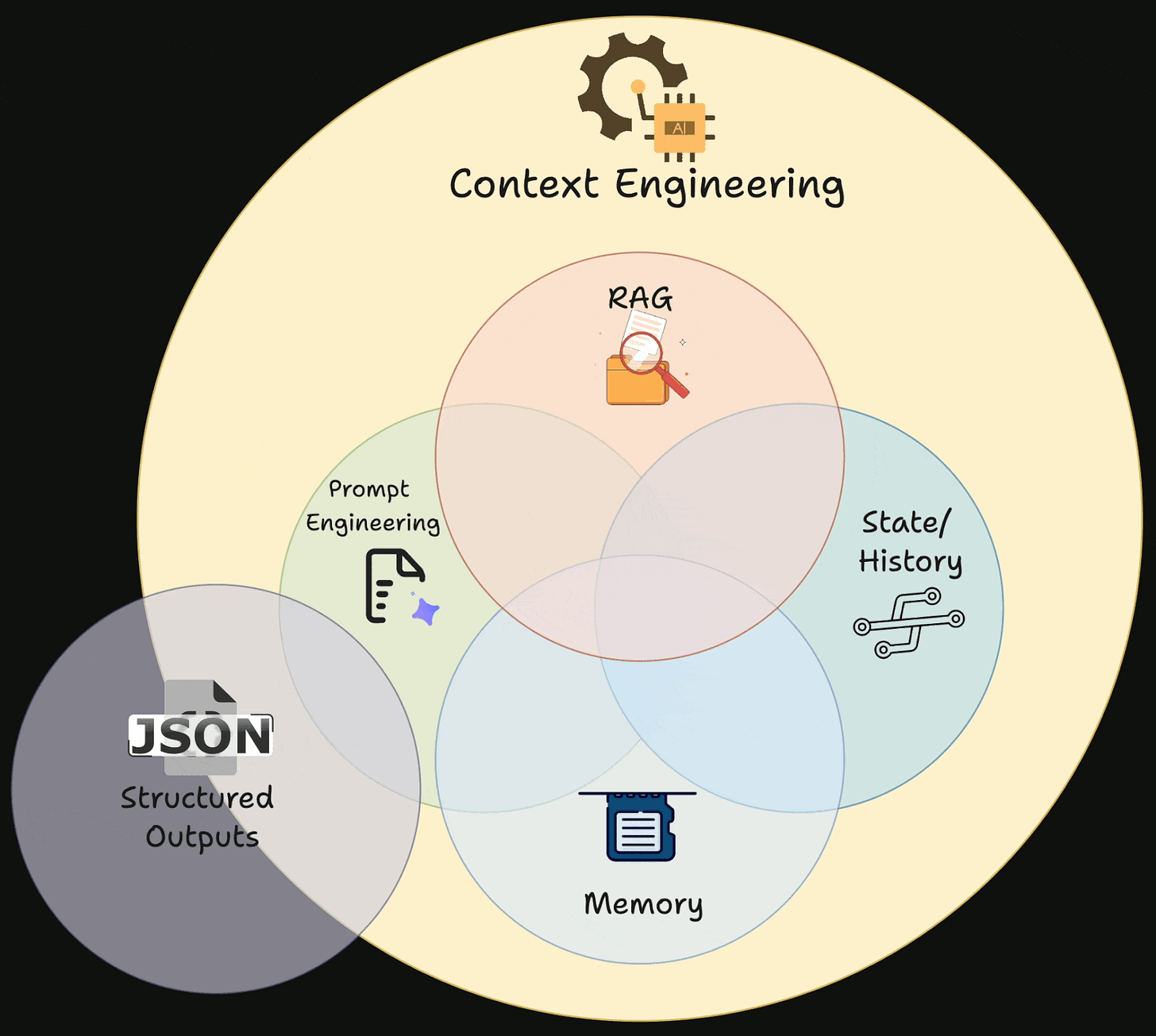

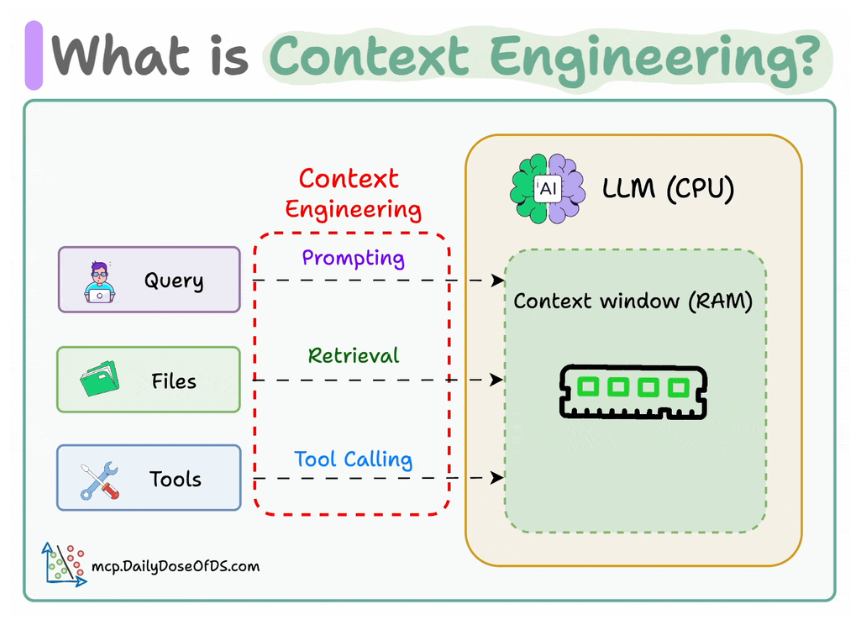

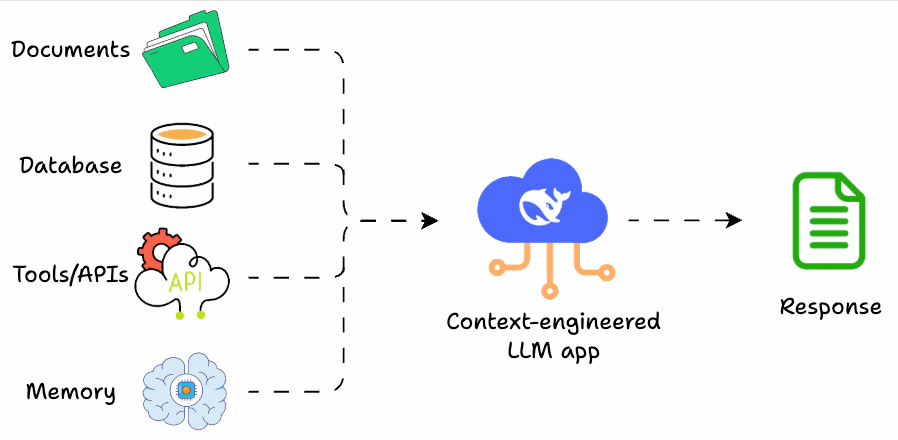

Context engineering can be understood as a collection of methods and techniques used to supply information and instructions to large language models in a deliberate and structured way.

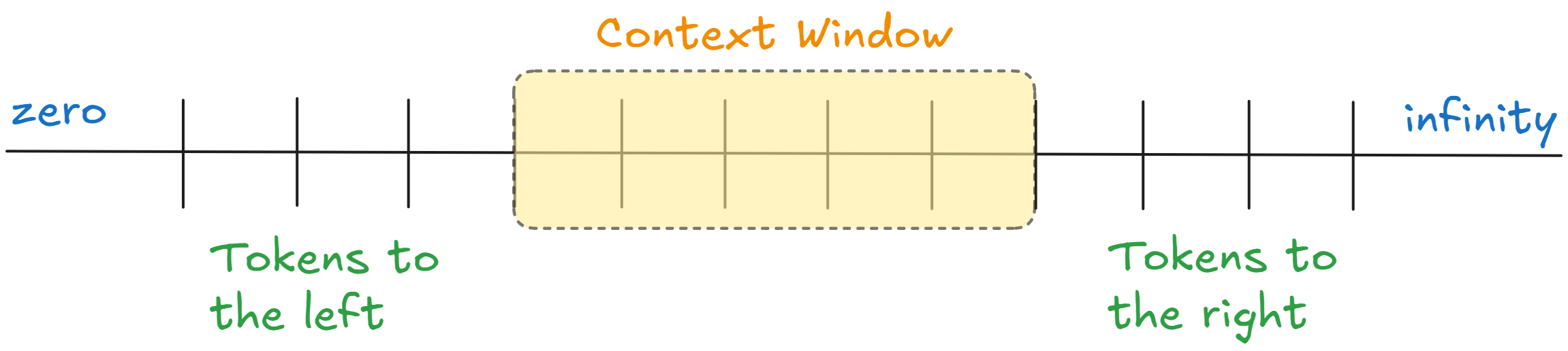

An LLM’s context window functions like its working memory. It contains the prompt, response, recent conversation history, retrieved knowledge, etc. This window is finite, which makes efficient use of that space critical.

Context engineering is therefore about maximizing signal within limited capacity, deciding what information to include for a given model invocation, what to leave out, and how to structure what remains so the model can reason effectively.

The ultimate goal of context engineering is to bridge the gap between a static model and the dynamic world in which an application operates. Through context, the model can be connected to external knowledge via retrieval, to past interactions via memory, to real-time data or actions via tools and perception, and to user-specific details such as preferences or profiles.

In production systems, this is what often determines whether an AI system feels intelligent and useful, or disconnected and unreliable.

Now, to make this more concrete, let’s establish a taxonomy of context types that we might include in an LLM’s input, depending on the use case.

Taxonomy of context

When we talk about “context” for LLMs, it’s not one monolithic thing. We can break it down into categories, each representing a type of information that might be included in the model’s input.

Here’s a taxonomy of context often considered in LLMOps:

Instruction context

This is the part of the input that tells the model what its task or role is. It includes the system prompt or any high-level directives. Essentially, it’s the instructions or rules governing the model’s behavior.

It usually does not contain factual data for the task itself, but rather sets the stage and defines how the model should operate (persona, style, boundaries, etc.). Instruction context is crucial to align the model’s responses with the desired tone and policy.

Without it, the model might default to a generic behavior or something undesired. In systems engineering terms, this is part of the configuration for the model on each request. It’s often static or changes infrequently.

Query or user context

This is the immediate input from the user: their question, command, or message. It defines the problem to solve right now. If we consider a chat, the latest user message is the core of the query context.

Knowledge context

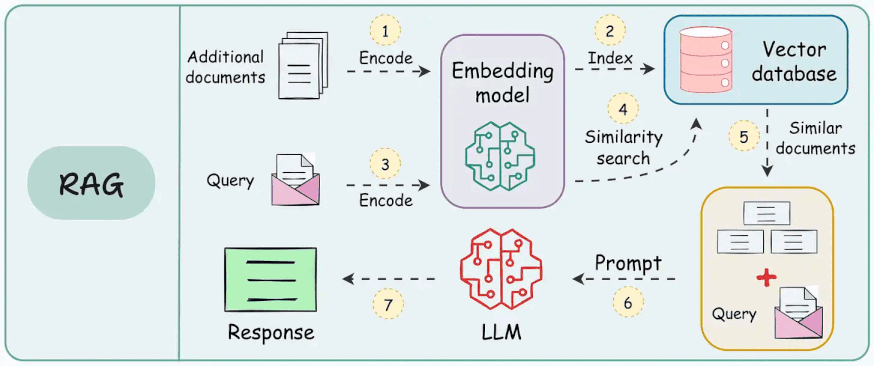

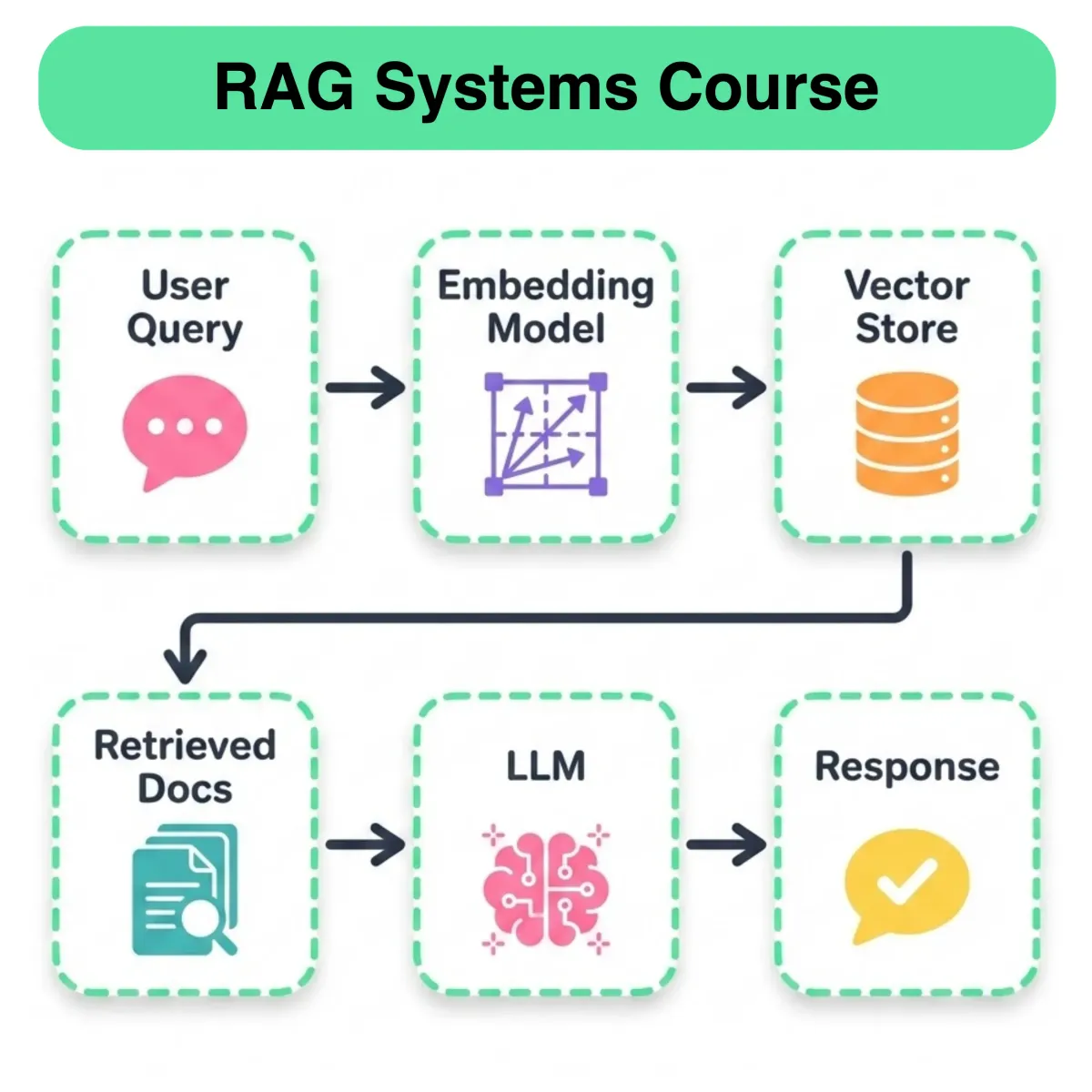

This is additional information provided to help answer the query, typically fetched from some database or documents. It’s often implemented via retrieval-augmented generation (RAG).

Knowledge context can include company documentation, knowledge base articles, textbook snippets, etc. It ensures the model isn’t just relying on parametric memory (which might be outdated or insufficient) but has access to the latest or specific facts.

For example, if a user asks “What’s our refund policy?”, your system might pull the refund policy text from your FAQ and include it in the prompt as context. When building pipelines, a lot of effort goes into getting this knowledge context right (finding the right pieces, chunking them, etc.).

Note: We'll not be covering everything about RAG in depth here, since we already have a detailed course on it. We recommend the readers unfamiliar with RAG checking that out:

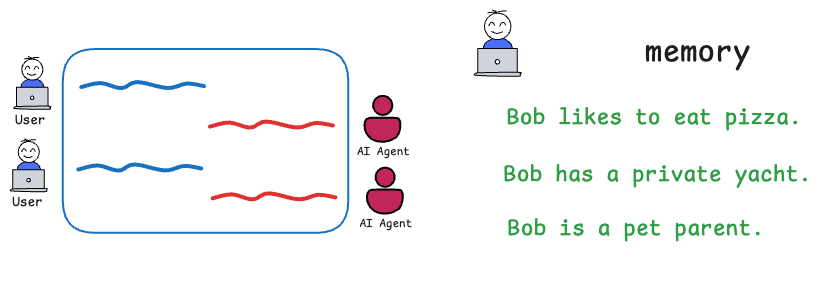

Memory context

This refers to including previous interactions or events so the model has continuity. In a chat scenario, the memory context would be the past dialogue turns that are relevant to keep the conversation coherent.

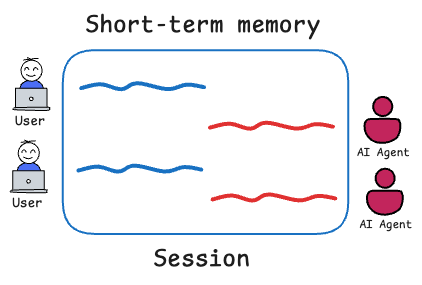

In a more general setting, memory might include things like what actions the agent has already taken, what the intermediate results were, or any conclusions already reached. Broadly, we break memory into:

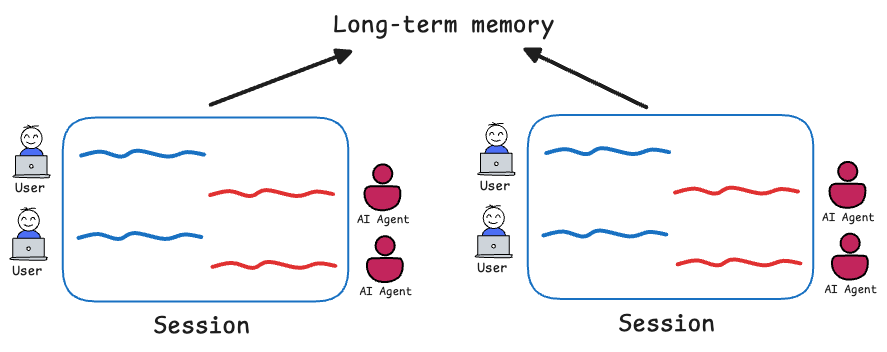

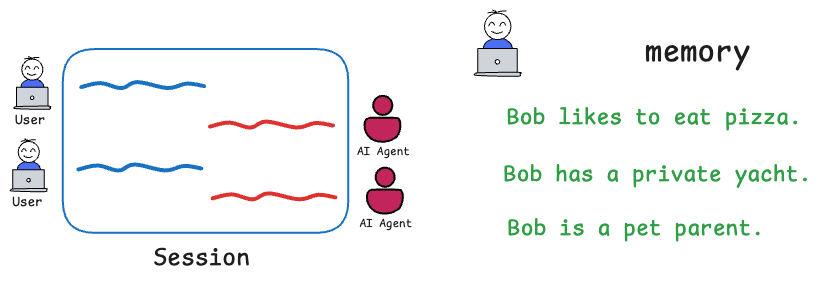

- Short-term: talks about what’s in the active prompt (or immediate context within the session).

- Long-term: knowledge and experience across sessions (or what’s stored elsewhere and fetched).

But conceptually, memory context is anything that happened before now that the model should “remember” in order to respond appropriately. For example, if earlier the user said their name or preferences, you want the model to remember that later in the session.

Or suppose if this is the 5th step in a multi-step response chain, the model should have the prior steps’ outcomes in context.

Checkout the articles linked below for a detailed discussion on memory for AI systems:

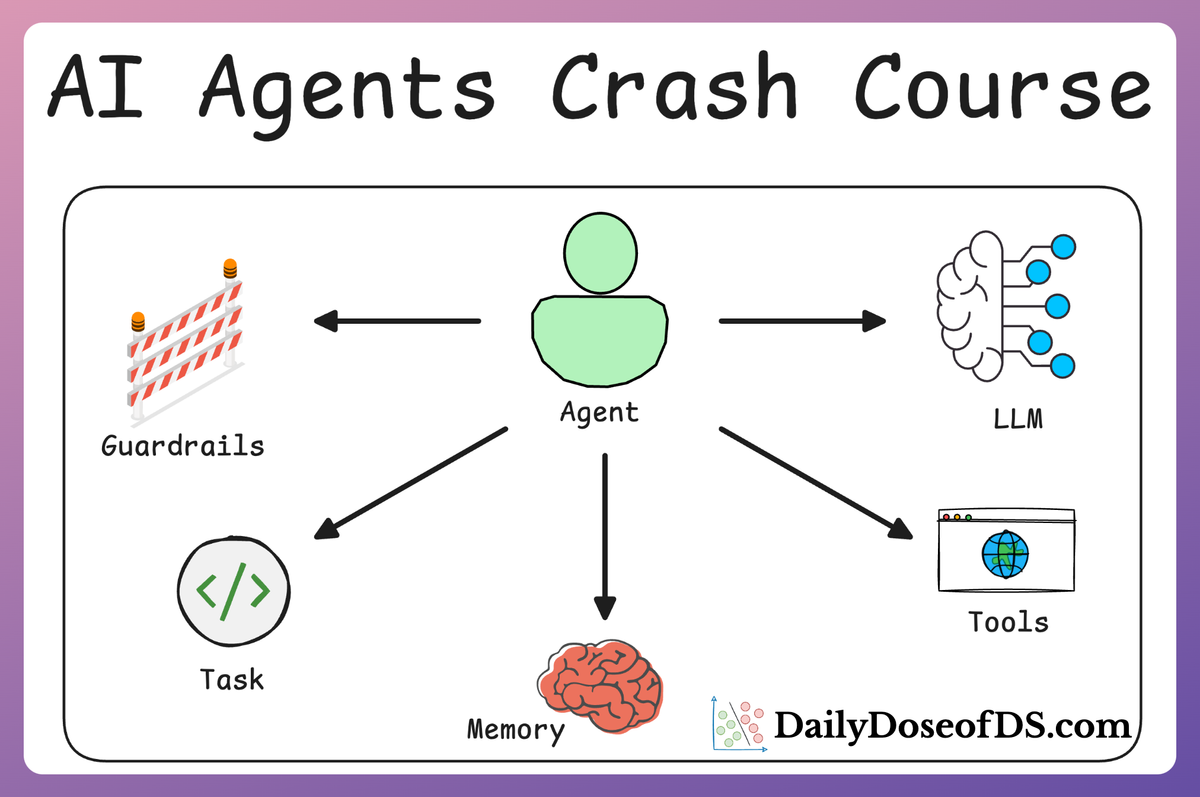

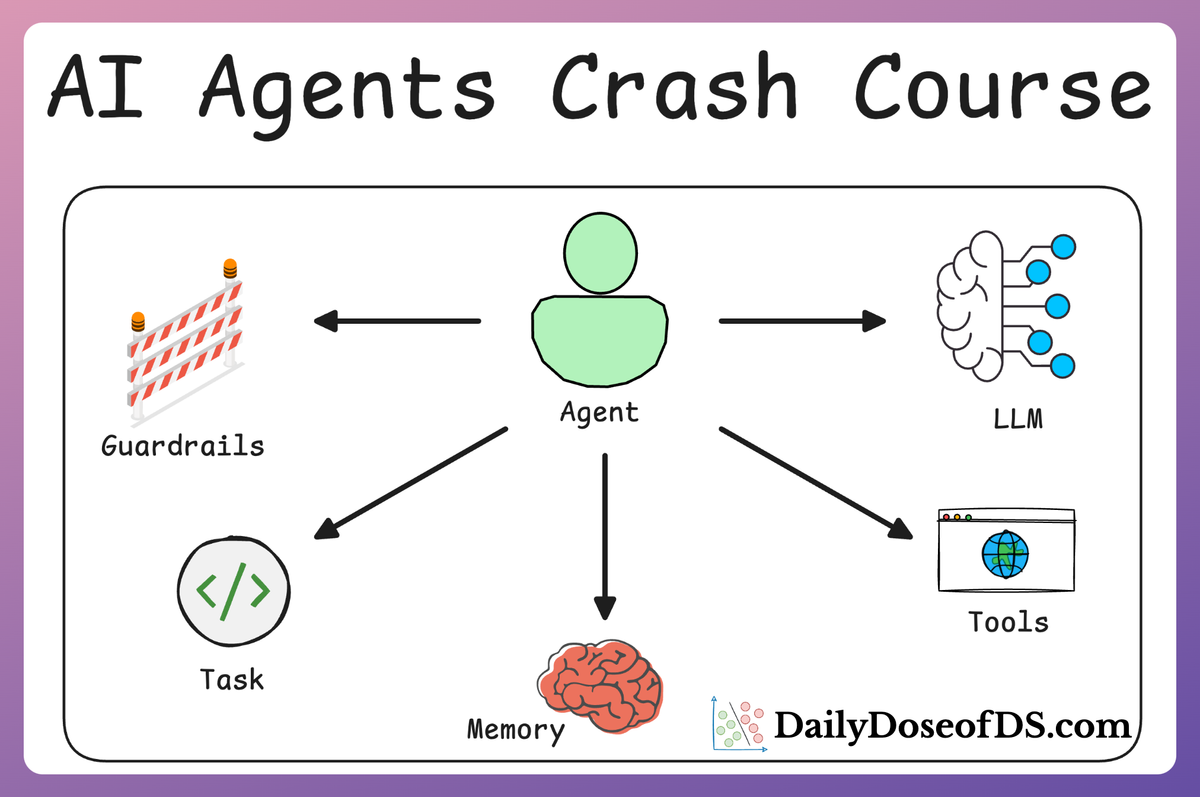

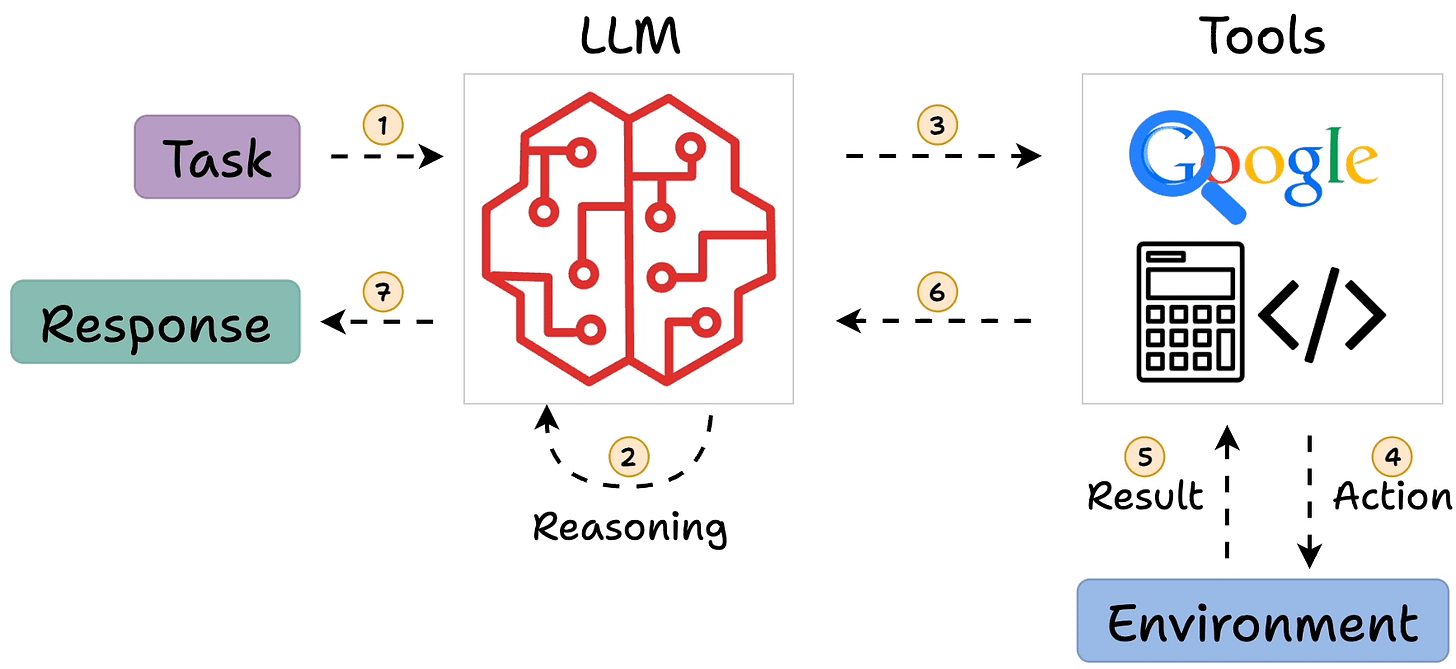

Tool context

When an LLM uses external tools (like search engines, calculators, databases, code execution), the outputs of those tools become context for the model. In an agent loop, after the model decides on an action and you execute it, you feed the result back into the model as an observation. This is context in the sense that it’s additional info. given to the model mid-task.

For instance, the model says “Action: call weather API for London today,” your system does it and gets “It’s 15°C and sunny,” and then you supply to the model: “Observation: 15°C and sunny in London.” Now the model has that data in its context for the next step, perhaps to report it to the user.

Tool context thus is a dynamic, often real-time form of context that expands what the model can do beyond its training data.

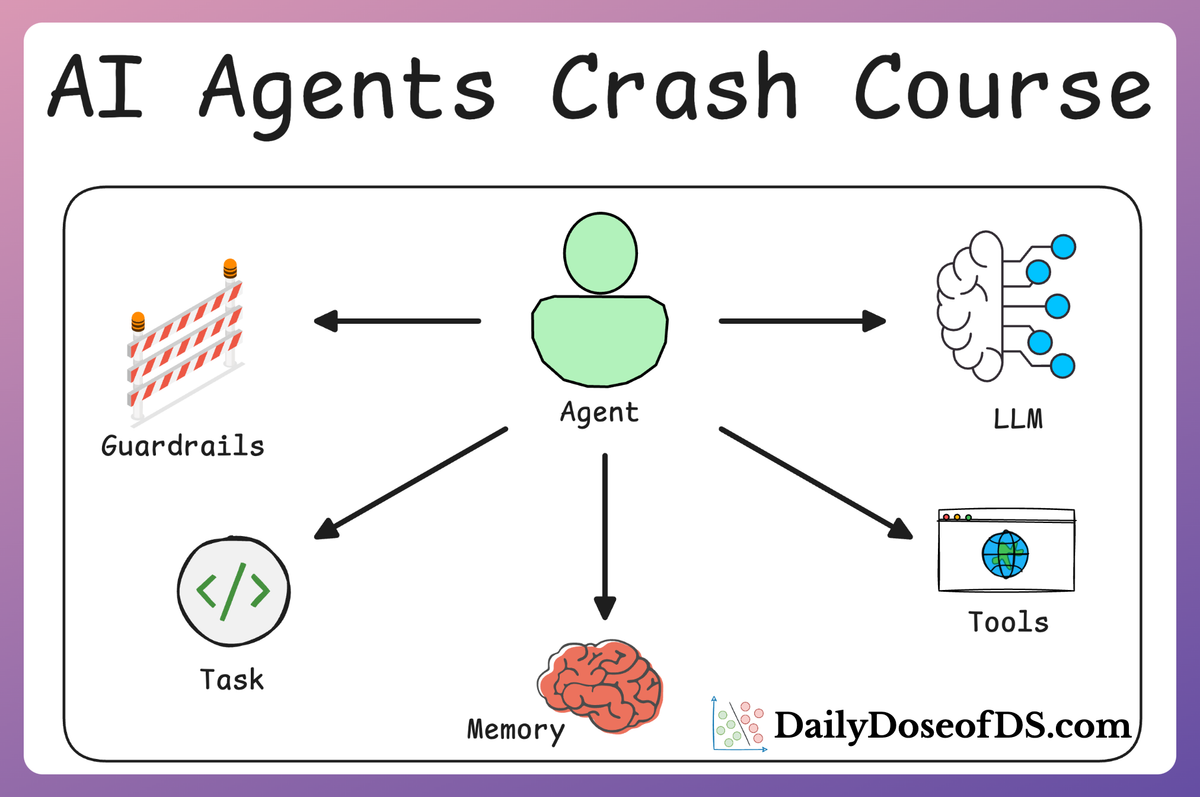

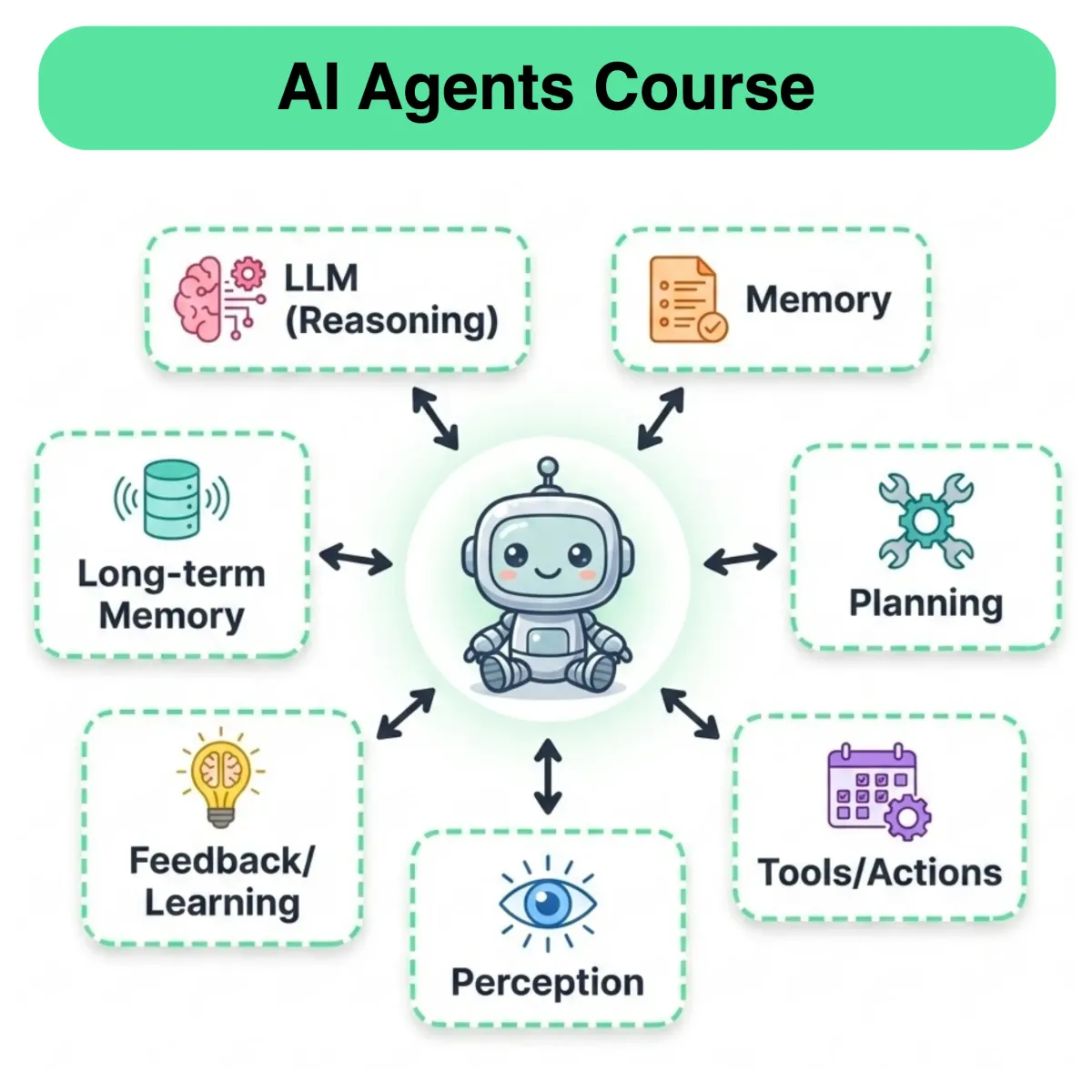

Note: We'll not be covering tooling in depth here, since we already have detailed discussion on tool use with LLMs as part of our Agents and MCP courses. We recommend the readers unfamiliar with tooling checking out the AI Agents course:

User-specific context

This category includes any information tailored to the specific user or session that can help personalize or contextualize the response. It might be a user profile (e.g., their name, location, membership status), their past interactions or preferences, or even dynamic context like current date/time as it relates to the user (maybe the user’s local time for greeting, etc.).

Including user-specific context allows the model to tailor answers, for instance, if you know the user’s proficiency level is beginner, you might include that as context: “The user is a beginner in programming.” Then the model can adjust the complexity of its answer accordingly.

Another example: if the user has an open support ticket, the context might include summary of that issue so the model doesn’t ask them to repeat it.

Environmental/temporal context

Sometimes listed separately, this includes things like the current date and time, the platform or device info., or other environmental variables that might influence the model’s response. For example, telling the model "Today’s date is 2026-01-19". Why do this? If the user asks “Is the event coming up soon?”, the model knowing today’s date can determine that.

Now that we have defined the different types of context, let’s move on to some important techniques and principles for context construction and management of these different context elements.

Principles and techniques for context construction

Context construction involves several principles and techniques to assemble model input from multiple information sources.

Rather than a single fixed procedure, real-world systems employ modular, conditional stages that are composed differently depending on the query, task, and operational constraints.

This section surveys commonly used techniques in practice, with a particular focus on retrieval-centric context assembly.

Typical modules/stages involved: