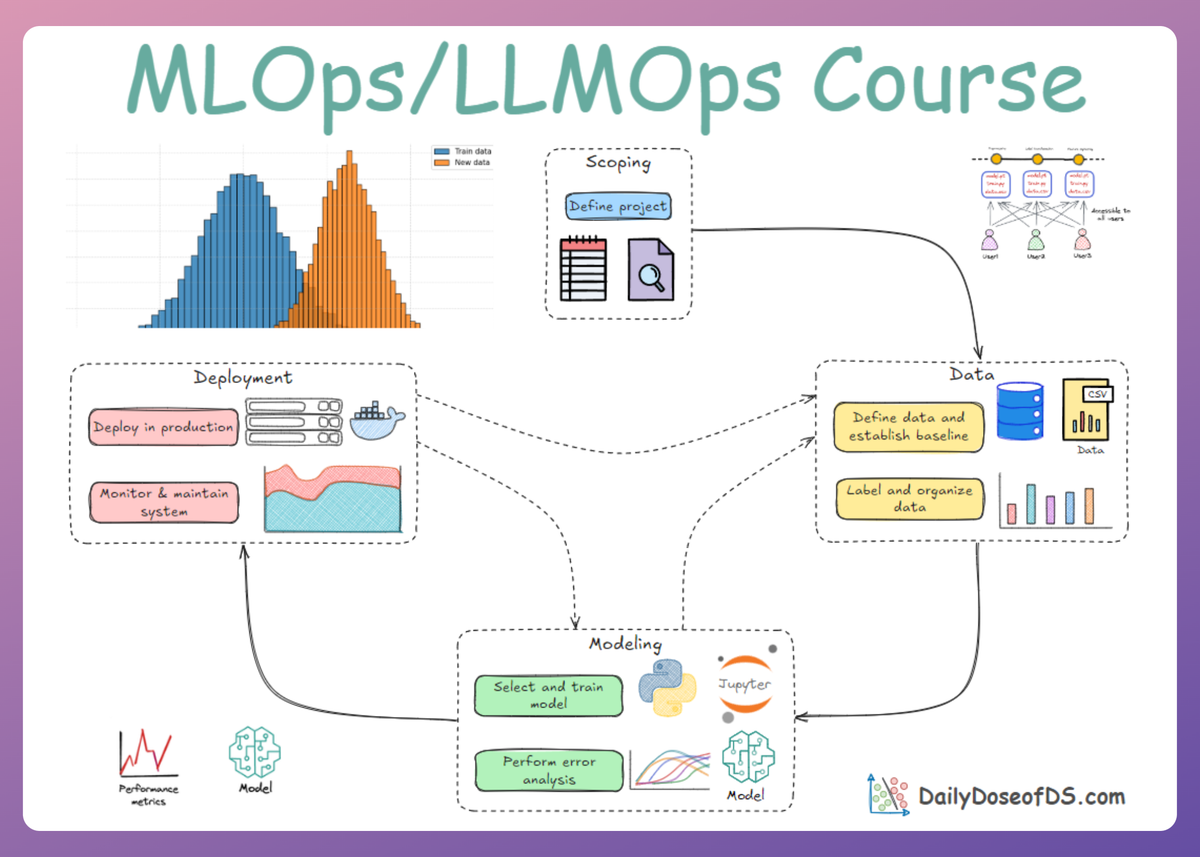

Context Engineering: Memory and Temporal Context

LLMOps Part 8: A concise overview of memory, dynamic and temporal context in LLM systems, covering short and long-term memory, dynamic context injection, and some of the common context failure modes in agentic applications.

Recap

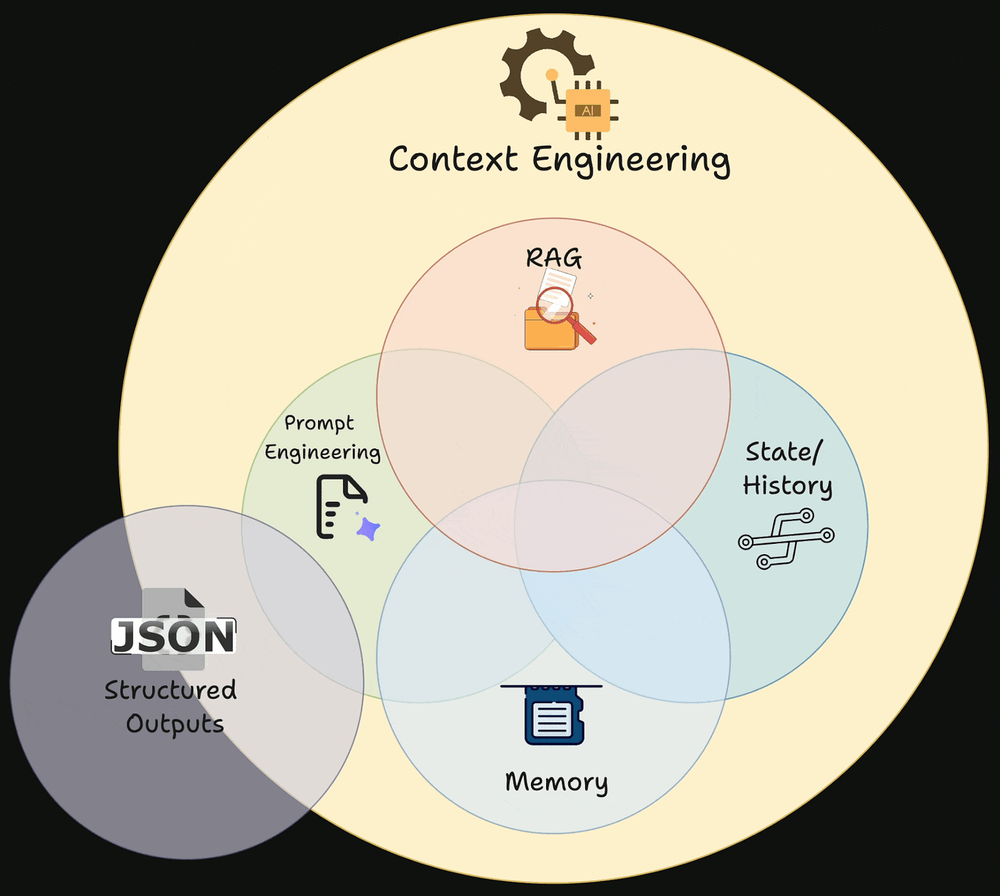

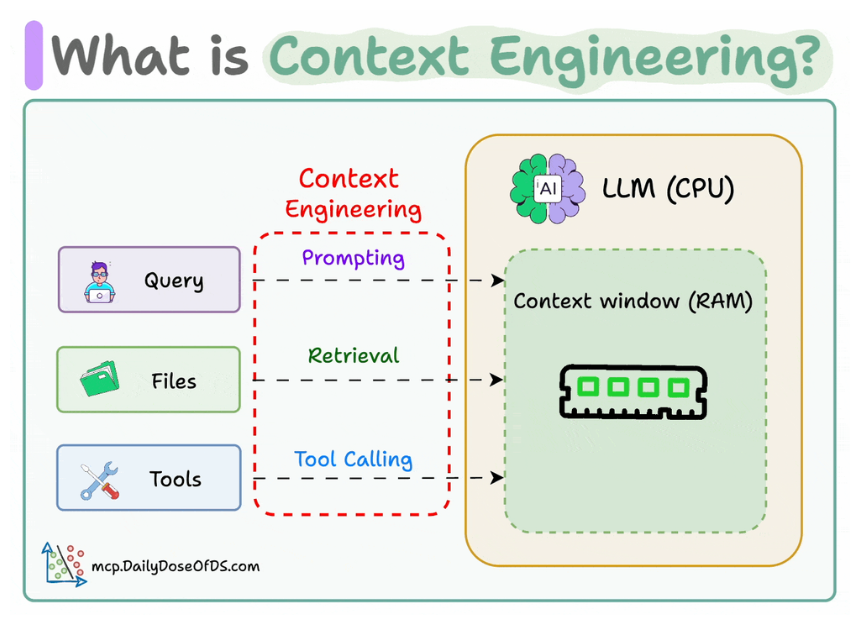

In the previous chapter (part 7), we explored the discipline of context engineering: the practice of designing the information environment in which an LLM application operates.

We began by reframing the context window as a form of working memory, and showed why the core job of context engineering is maximizing signal under strict capacity constraints.

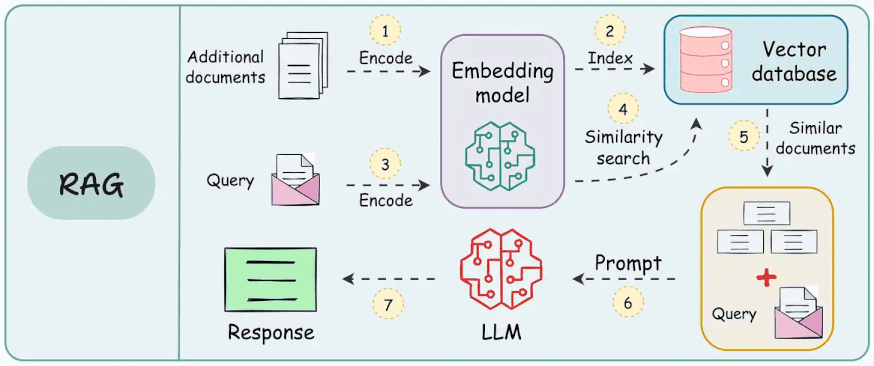

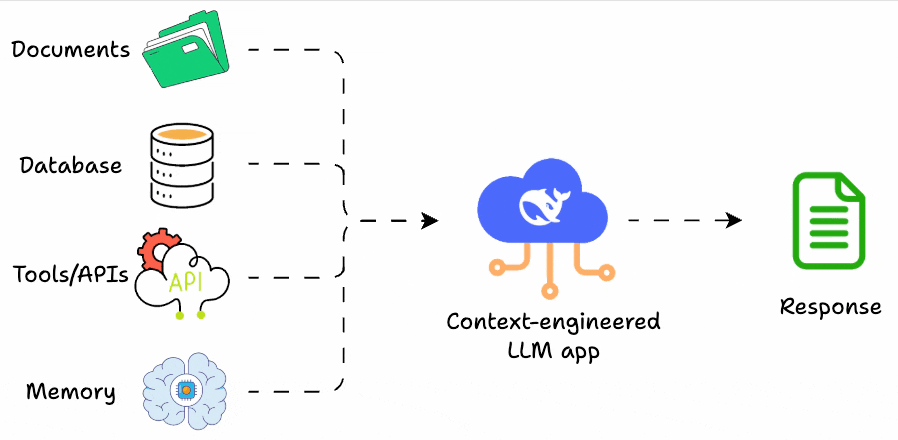

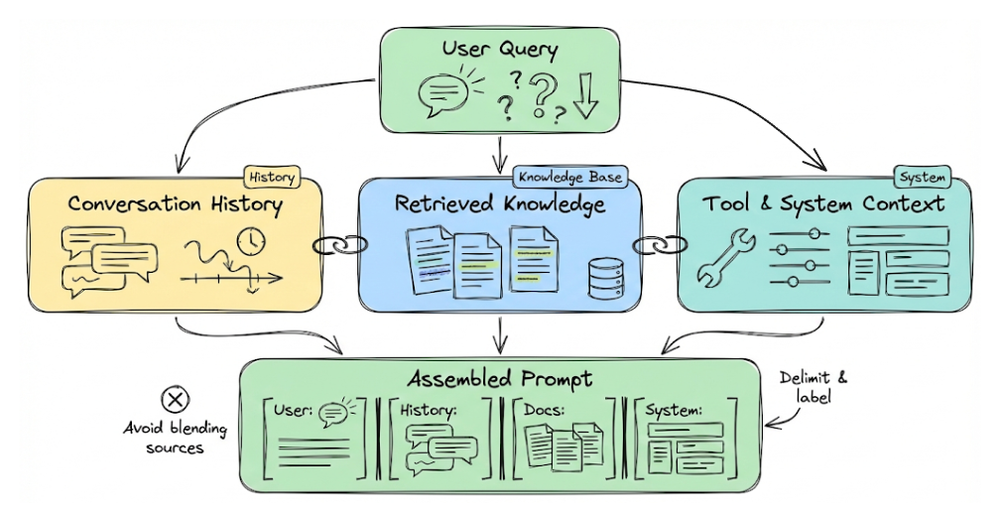

From there, we built a practical taxonomy of context types that show up in real systems: instruction context, query context, knowledge context (RAG), memory context, tool context, user-specific context, environmental and temporal context.

Next, we moved from "what context is" to "how context is constructed". We introduced modular, conditional context construction.

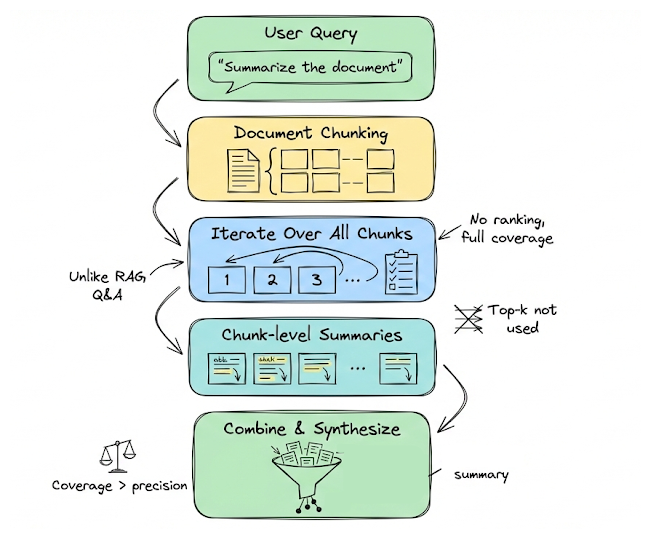

We explored chunking as a core design decision and walked through modern chunking strategies. We also clarified how chunking behaves differently for summarization-style workloads, where coverage replaces relevance as the optimization goal.

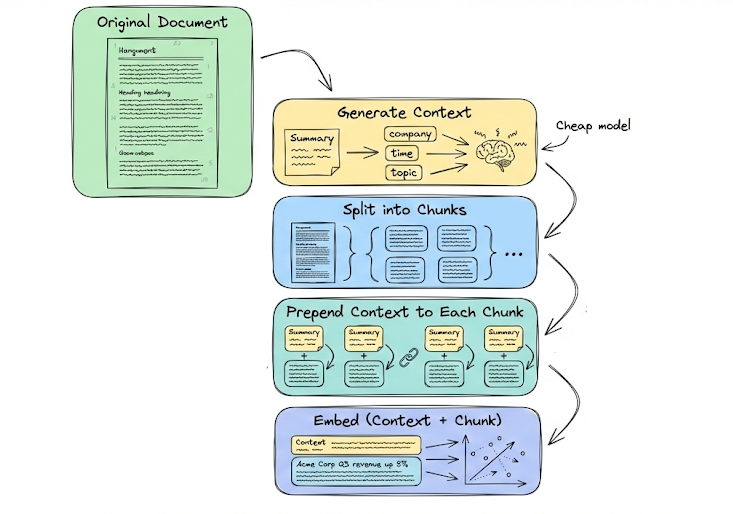

We then covered the standard retrieval stack: vector search as a candidate generator, the need to tune precision vs. recall, and improvements like contextual retrieval.

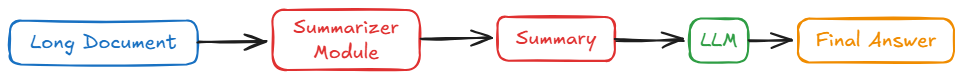

After that, we introduced summarization and context compression as context management tools, and discussed query-guided summarization, filtering, deduplication, structured compaction, and prompt compression techniques like LLMLingua.

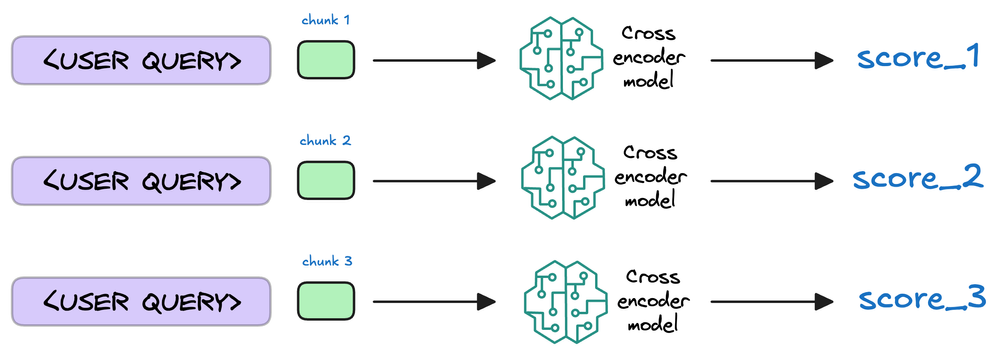

Moving ahead, we examined re-ranking and selection, especially the common bi-encoder + cross-encoder pattern that retrieves broadly and then tightens precision with a slower but more accurate scorer.

Next, we also explored governance and assembly. The core takeaway was that context construction is not a single step, it is an engineered pipeline that balances relevance, coverage, and efficiency.

Finally, we ended with three hands-on demos:

- Semantic and AST-based chunking

- Bi-encoder retrieval with cross-encoder re-ranking

- Prompt compression with LLMLingua.

By the end of the chapter, we had moved from thinking of context as “extra text in the prompt” to seeing it as a structured, retrieval-driven, and governable system component, one that often determines whether an LLM application feels intelligent and dependable, or noisy and brittle.

If you haven’t yet gone through Part 6, we strongly recommend reviewing it first, as it helps maintain the natural learning flow of the series.

Read it here:

In this chapter of discussing context engineering we will explore selected aspects of memory in LLM applications and dynamic and temporal context.

As always, every notion will be explained through clear examples and walkthroughs to develop a solid understanding.

Let’s begin!

Memory systems

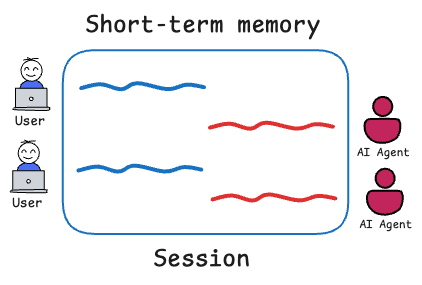

Humans have short-term and long-term memory; analogously, AI systems with LLMs can benefit from a notion of short-term context and long-term memory.

Short-term memory

By short-term we usually refer to the immediate context within the session or more precisely, what's part of the "active" prompt. This is basically the conversation history or any information stored directly in the prompt for the current inference.

It’s ephemeral by nature. Short-term memory covers the immediate dialogue (last few messages) and maybe a brief summary of earlier ones. It’s fast to access (the model reads it directly) but limited in capacity.

The design question is often how much of the recent conversation to include verbatim. A common approach is to do something like: include the last N turns. If over limit, start trimming the oldest. This works to keep coherence for recent references, but if the user goes “N messages ago we said XYZ”, the model might have already dropped that from short-term memory.

Here, as mentioned earlier, systems typically combine recent verbatim dialogue with a rolling summary of older context. But when even summaries start getting too generic and/or trimming is unavoidable, long-term memory is used to reintroduce relevant information (memories).

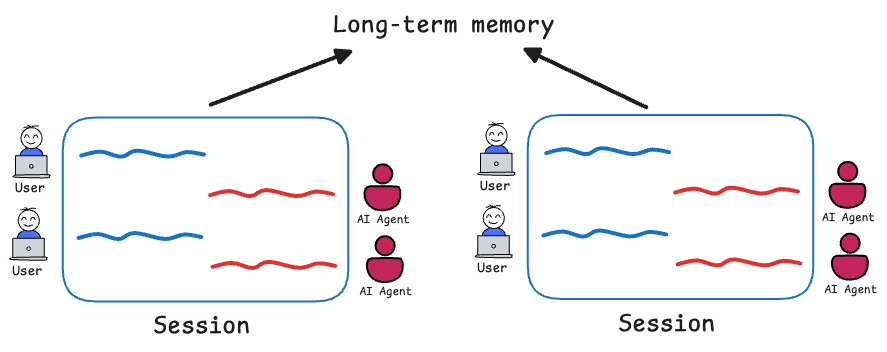

Long-term memory

This refers to information retained across sessions or that persists even as short-term context moves on. Typically implemented via external storage: a vector database (or a vector store, depending on use case) for semantic memories, a relational DB for structured data, etc.

Long-term memory allows the system to recall things that were said or learned earlier. For example, a support chatbot could “remember” a customer’s issue from yesterday when they come back today by looking it up in a user memory store.

In other words: persistent memory must be loaded into working memory before the model can reason over it.

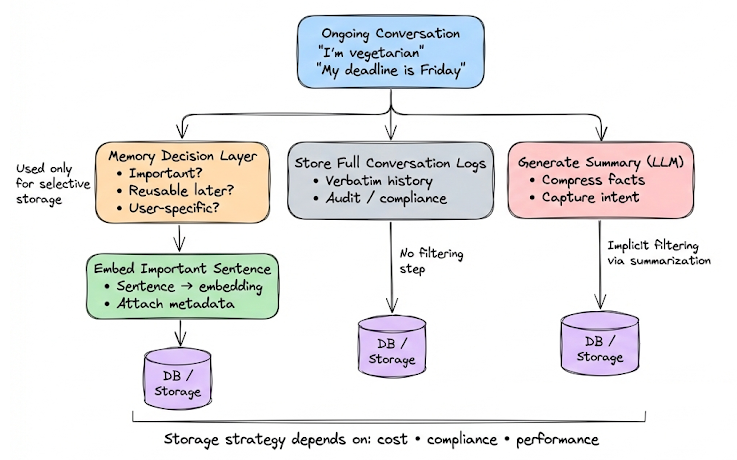

Approach

Whenever something potentially important comes up in conversation (like the user shares a piece of information that could be useful), you embed that sentence and store it in a vector DB with metadata.

Later, you query the vector DB with the new user query to see if any stored information is relevant.

What to store in long-term memory

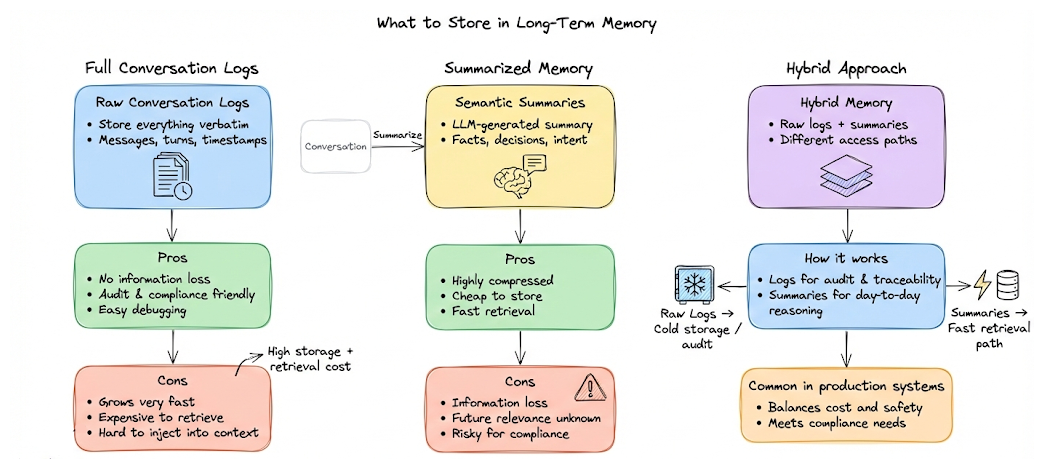

A core design decision is what actually gets stored. One option is to persist full conversation logs verbatim. This is the safest choice from a compliance, audit, or debugging perspective, because nothing is lost. The downside is obvious: raw logs grow quickly and are expensive to retrieve and inject into context.

A common alternative is to store summaries instead. After a conversation (or after a logical phase), the LLM generates a concise semantic summary capturing information, decisions, facts, and intent. This drastically compresses memory and keeps retrieval lightweight. The trade-off is information loss: details that seem unimportant today may become relevant later especially for compliance-sensitive use cases.

Hence, in practice, many robust (and compliance-sensitive) systems do both: full logs + summaries.

Full logs are archived in cheaper storage for safety, traceability and compliance, while summaries are what actually get retrieved and injected into prompts. This gives you compression for runtime use without permanently discarding information.

When to retrieve long-term memory

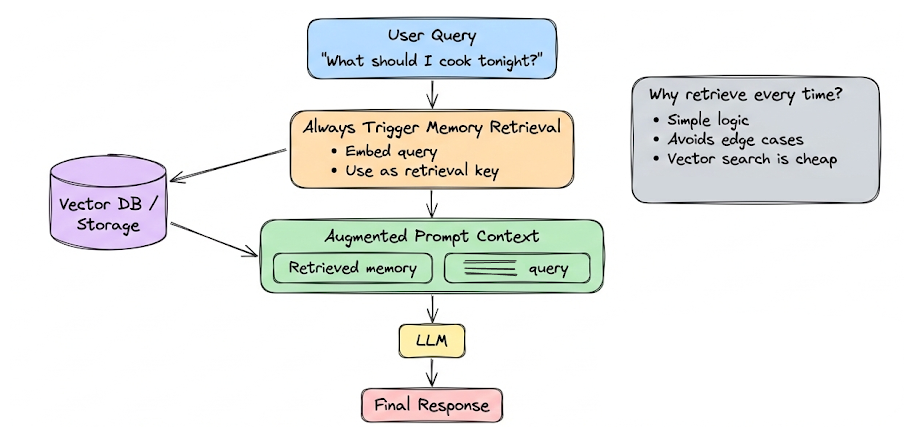

The simplest strategy is to retrieve long-term memory on every user query, using the current query (or conversation state) as the retrieval key. This is common because vector search is relatively cheap, and it avoids edge cases.

That said, if the conversation is clearly staying within a single topic for a while, you could retrieve memory only once at the start of that topic and reuse it across turns. This slightly reduces overhead but adds logic and state management complexity.

Caching retrieved memory

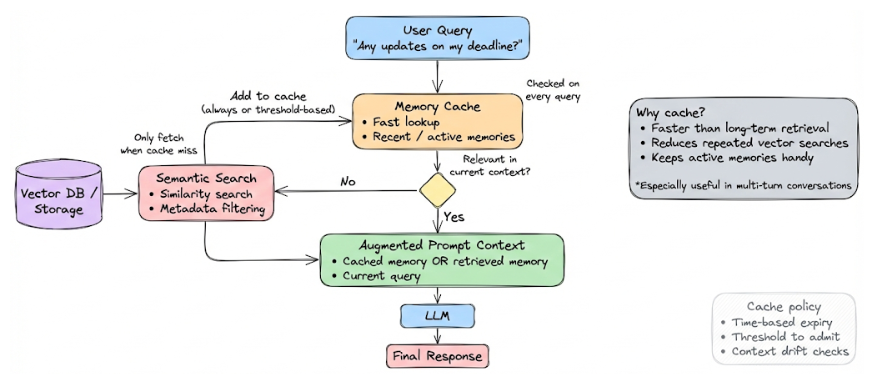

Another robust and widely used pattern is to introduce a memory cache that sits between the model and long-term storage. Instead of retrieving from long-term memory on every query, the system first checks this cache.

When relevant memories are fetched from long-term storage, they may be added to the cache directly or based on some threshold. For subsequent user queries, the system consults the cache first. If the cached memory is still relevant to the current conversation state, it can be reused directly without performing another long-term retrieval.

This has a few important benefits. It reduces repeated vector searches for the same information, overall lowers latency, and simplifies prompt construction during continuous conversations on the same topic. It also creates a natural separation between "active" context (what’s currently in use) and "archived" context (everything stored long term).

If the cache lookup fails or confidence in relevance drops, the system can always fall back to long-term memory retrieval and refresh the cache accordingly. In practice, this pattern gives you most of the robustness of per-turn retrieval while being more efficient and easier to reason about during multi-turn interactions.

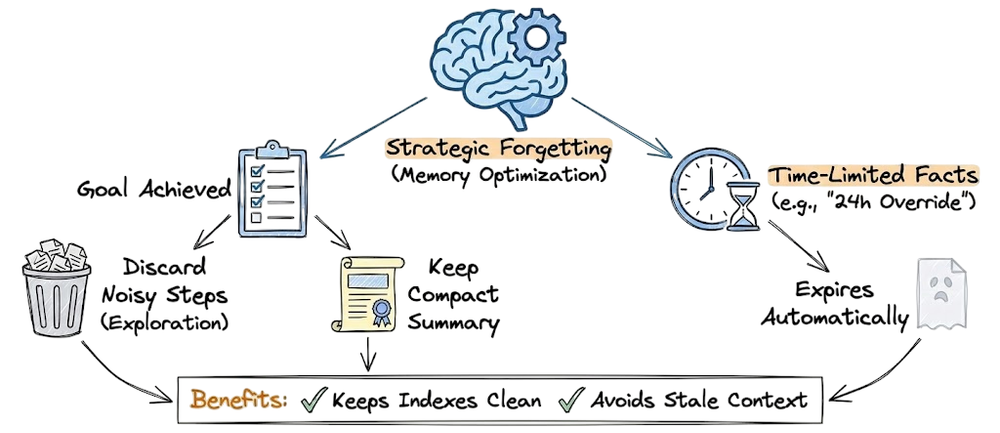

Memory pruning and cleanup

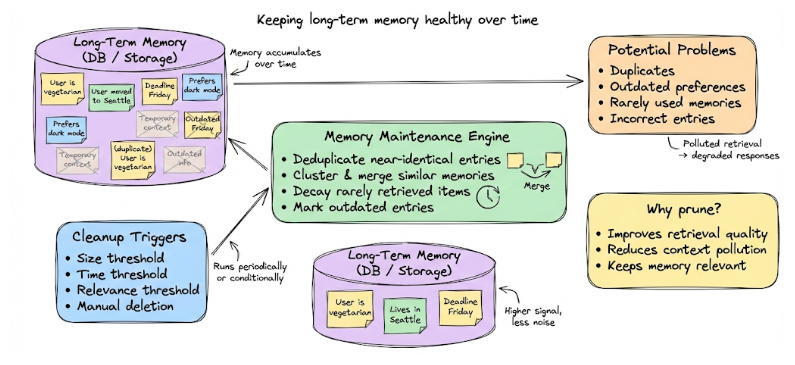

Over time, long-term memory can accumulate noise: duplicated facts, outdated preferences, temporary context that no longer matters, or even incorrect entries. If left unchecked, this can pollute retrieval and degrade response quality.

To prevent this, memory systems should support pruning and maintenance, such as:

- Deduplicating near-identical entries

- Clustering and merging semantically similar memories

- Decaying or removing memories that are rarely retrieved

- Marking entries as outdated based on time or newer conflicting information

Cost considerations

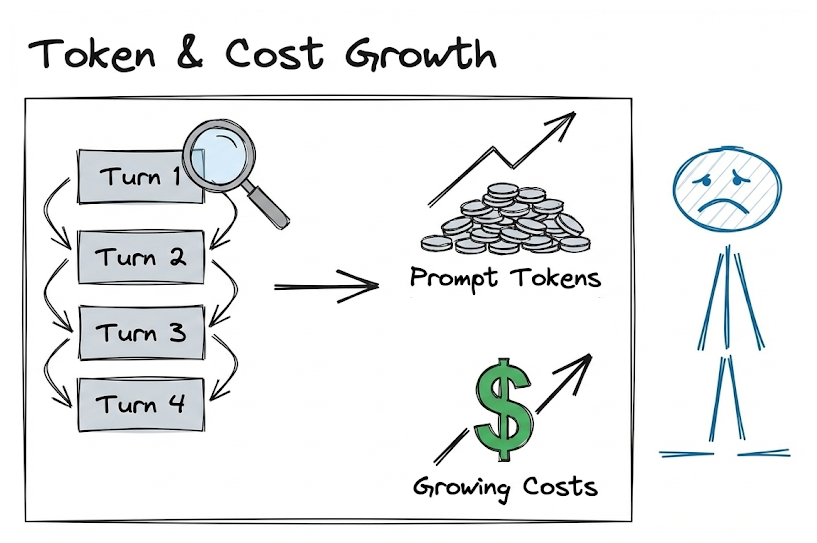

Long-term memory adds cost in two places: storing embeddings and performing vector searches. However, these costs are usually modest compared to calls we make to LLMs, compounding token costs (especially in a fully sequential setup and multi-turn conversations).

In fact, effective memory retrieval can reduce overall cost. By injecting the right context early, the model is less likely to ask follow-up clarification, hallucinate, or drift off topic; each of which would otherwise require extra tokens and extra model calls.

The real cost is often complexity, not money. Memory systems require careful design, evaluation, and maintenance to ensure they help in the manner intended.

In summary, a well-designed memory system (short-term + long-term) extends the effective context of the LLM beyond a fixed window, enabling continuity and accumulation of knowledge over time. It’s a key part of context engineering for any stateful AI interaction.

Next, let’s discuss injecting dynamic and temporal context.

Dynamic and temporal context injection

So far, we talked about fetching context in a fairly static way (stored memory). But many applications require injecting dynamic context, information that changes with time or is generated on the fly, into the model’s prompt.

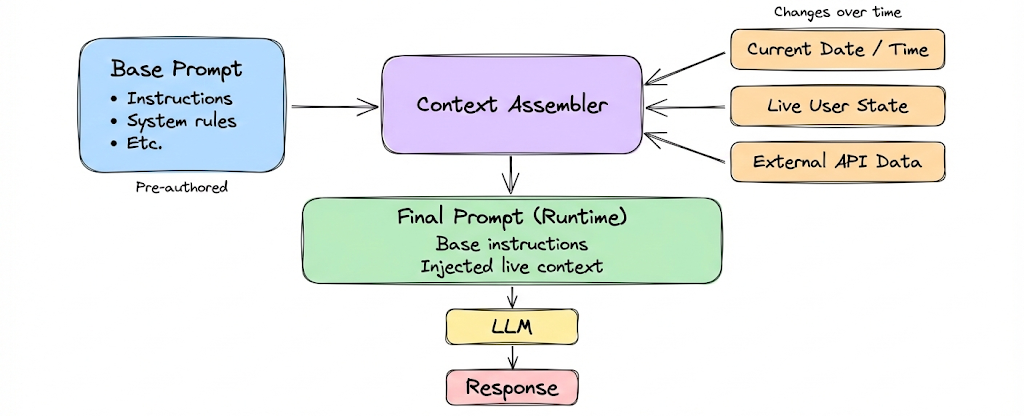

Dynamic Context means the context is not pre-authored or stored, but assembled or updated in real-time based on the current state.

Examples:

- The current date/time: Many prompts explicitly include date to help the model avoid confusion with its training cutoff and handle temporal questions.

- Real-time data: If a user asks “What’s the stock price of X right now?”, you need to fetch that via an API. The result is dynamic context, it didn’t exist until now. Similarly, weather info, news headlines, latest database entries; all are dynamic.

- User’s current interaction state: If the user is filling a form and the model assists, the partially filled fields could be dynamic context on each turn. Or in a code assistant, the current file contents or cursor position is context that changes as user edits.

- Tool results: In an agent performing actions, each time it runs a tool (API call, code execution), the output is new context fed in. That we covered under tool context, but it’s inherently dynamic because it’s a function of user input and current environment.

- Generative chain-of-thought: Some approaches feed the model’s own prior reasoning steps back in as context for further reasoning (like reflecting or refining). This is also dynamic self-generated context.

Temporal context specifically refers to context that has a time dimension:

- The simplest temporal context is the current date/time injection, as mentioned.

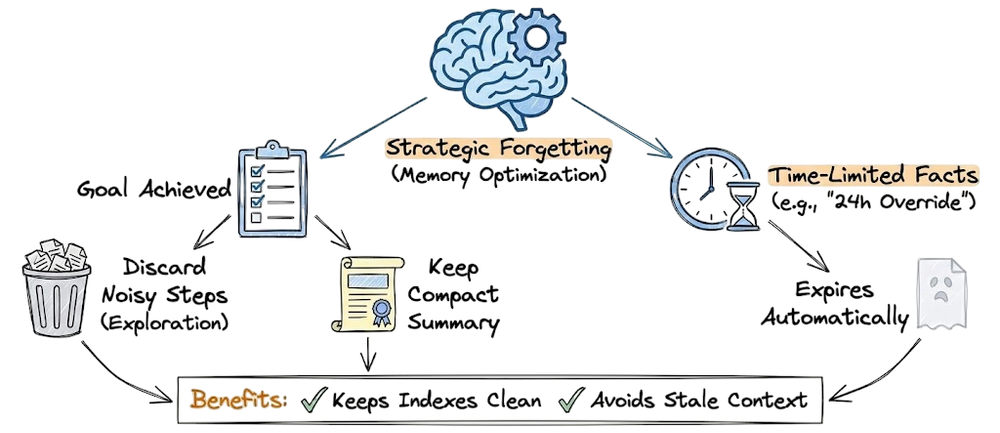

- Another is knowledge that decays with time, for example, “the current top trending topics on Twitter” changes daily. Hence, we might implement strategic forgetting for time-limited facts.

- Temporal memory: as conversations progress, older context might be summarized (as we talked), effectively injecting a “summary so far” at some regular interval. That summary can be considered a temporal context injection technique, you compress older context over time.

Injection methods

A few common dynamic and temporal context injection methods are:

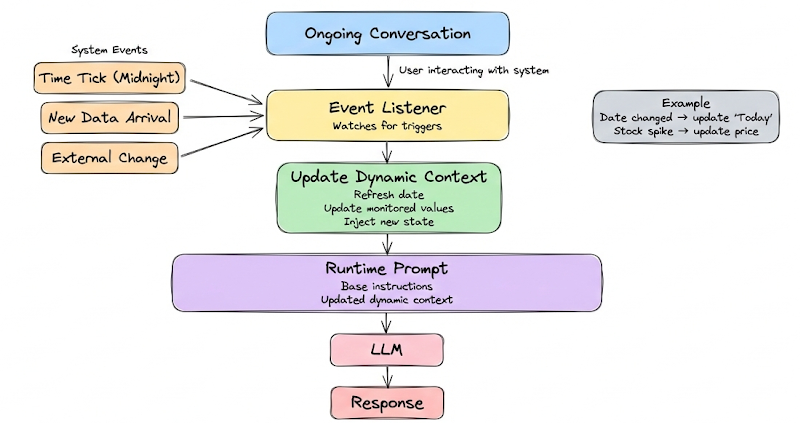

Event-driven context refresh

This means if certain events happen (time ticks, new data arrival), the context is updated.

For instance, if the conversation crosses midnight and date changed, maybe update the "Today’s date" context if it’s persistent. Or if a monitored data source (like stock price) changes significantly while the user is interacting, maybe spontaneously update context or notify the model. Usually though, it’s user-driven (user asks and system fetches at that time).

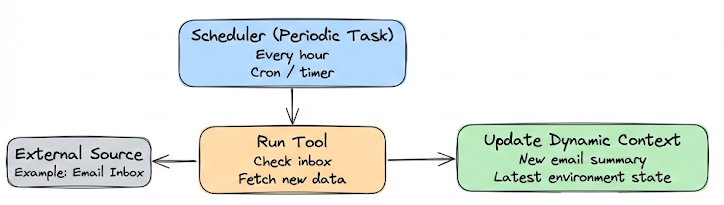

Scheduled context injection

In some agent scenarios, the agent might have tasks that run periodically and then feed results in.

For example, an agent that monitors an email inbox every hour and then in the next conversation turn mentions any new important email. That means the context pipeline might include a step “check for new emails (tool), if found, include summary in prompt.” So at different times, context content changes because environment changed.

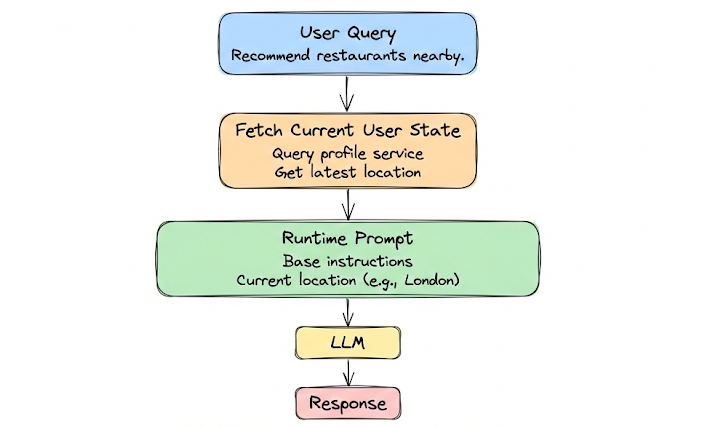

User-specific dynamic context

If a user’s current context like location changes (they moved to a different city), ideally the system knows and updates what it tells the model.

If location is used in answers, and user moves, you want “User is in London now” context instead of the old “User in Paris.” This could be handled by always querying a profile service for current information at prompt time.

Memory aging

We touched on summarization as one method. Another is strategic forgetting (dropping if assumed no longer needed). Some systems do “forget” intentionally things that are resolved or won't come up again, to minimize risk of retrieval picking up unnecessary stuff.