Building Blocks of LLMs: Tokenization and Embeddings

LLMOps Part 2: A detailed walkthrough of tokenization, embeddings, and positional representations, building the foundational translation layer that enables LLMs to process and reason over text.

Recap

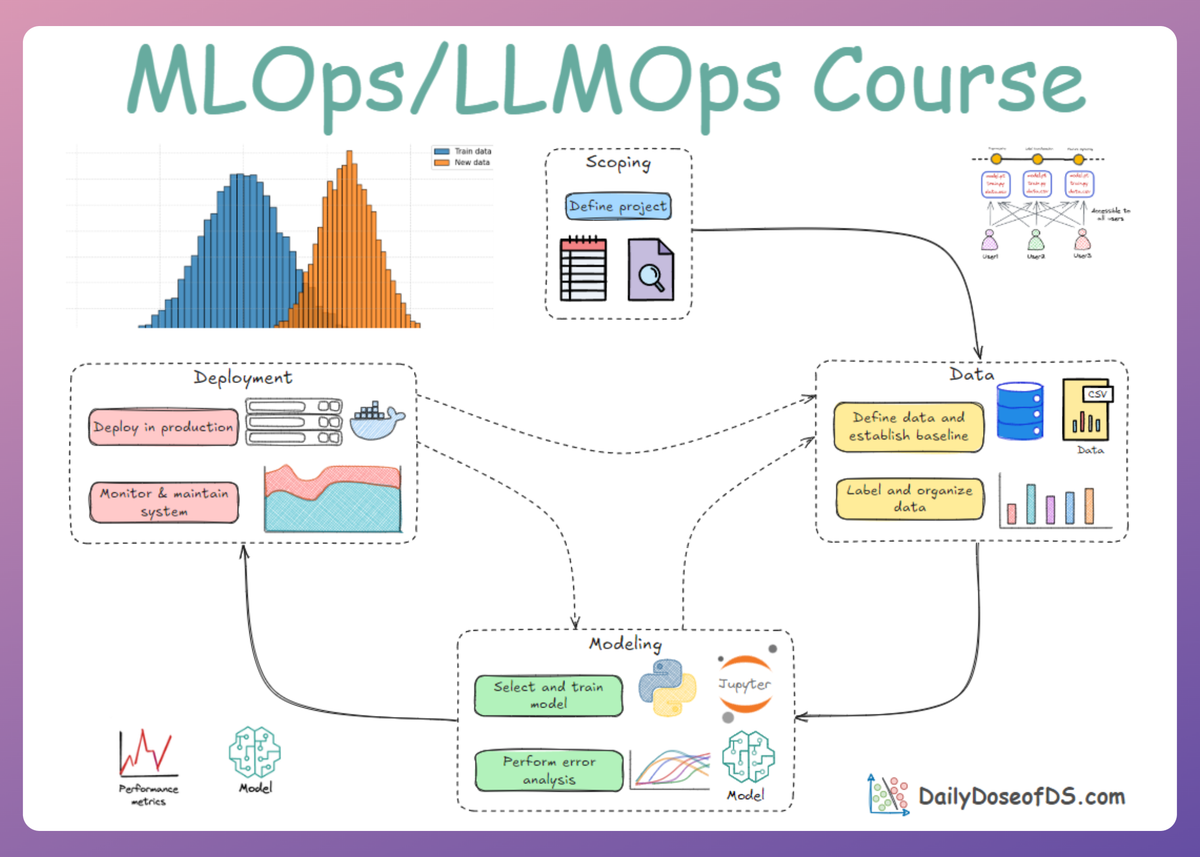

Before we dive into Part 2 of the LLMOps phase of our MLOps/LLMOps crash course, let’s briefly recap what we covered in the previous part of this course.

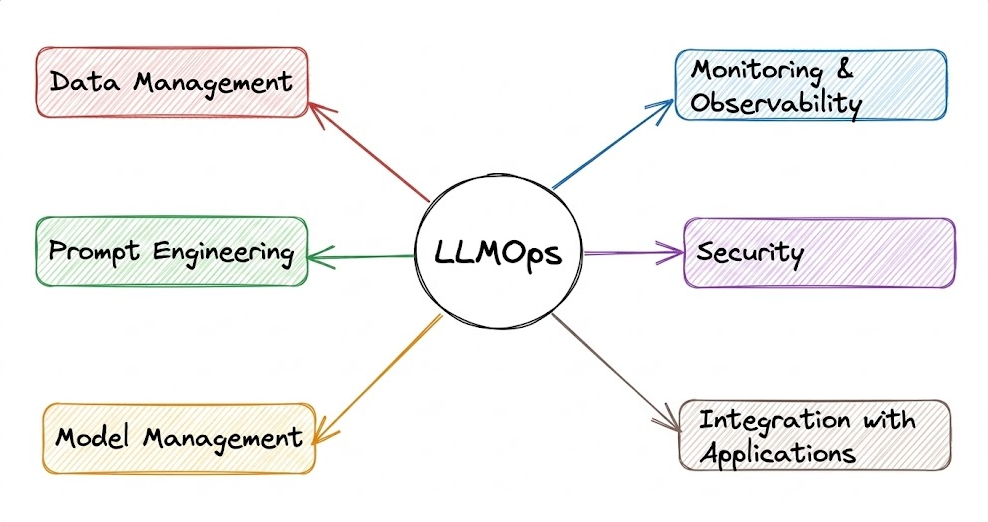

In Part 1, we explored the fundamental ideas behind AI engineering and LLMOps. We began by defining what LLMOps is and examining the goals it aims to achieve.

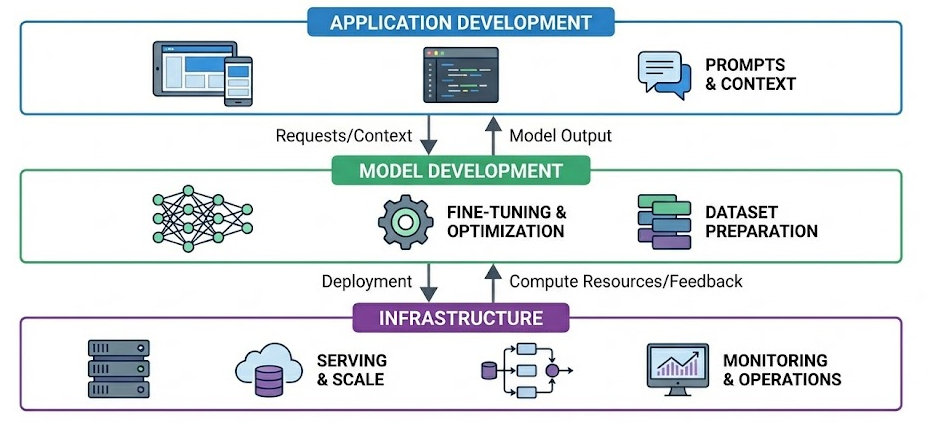

Next, we discussed foundation models and the AI application stack, focusing on its three layers.

After that, we explored several fundamental LLM concepts, including what “large” means in the context of LLMs, different types of language models, emergent abilities, prompting methods (zero-shot and few-shot), a brief overview of attention, and the limitations of LLMs.

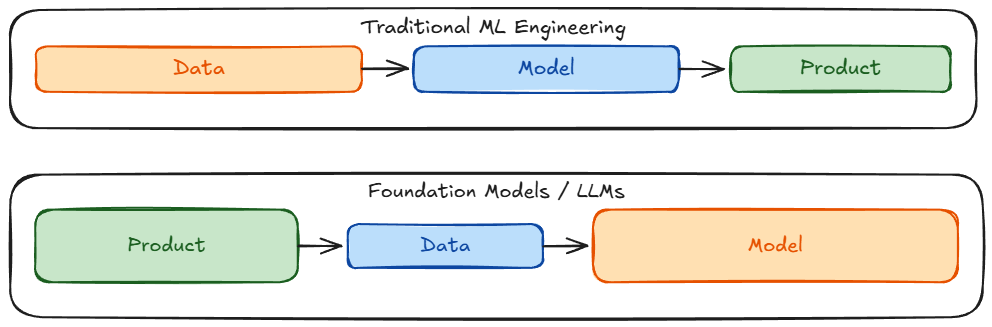

Next, we examined the shift from traditional machine learning models to foundation model engineering, highlighting key changes such as adaptation strategies, increased compute demands, and new evaluation challenges.

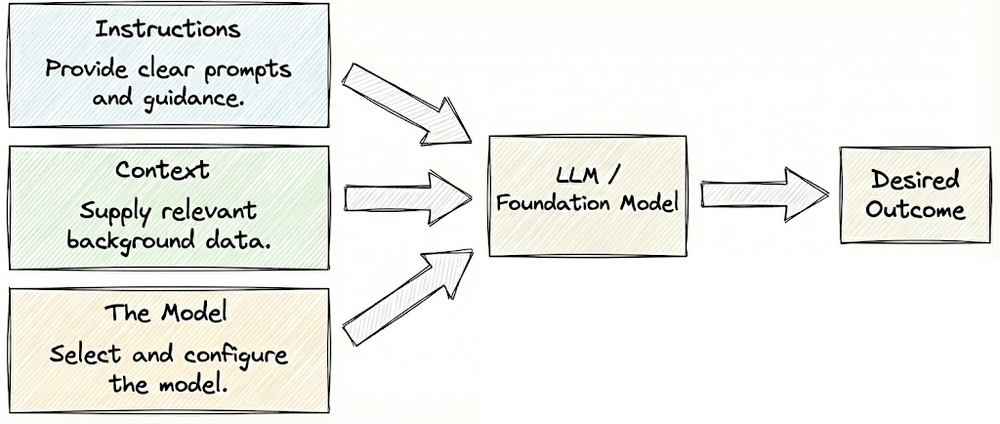

Moving forward, we examined the key levers of AI engineering: instructions, context, and the model itself. We begin by optimizing prompts; if that is insufficient, we enrich the system with supporting context. Only when these approaches fall short do we turn to modifying the model.

Finally, we took a brief look at the key differences between MLOps and LLMOps.

By the end of Part 1, we had a clear understanding that, despite differences from MLOps, foundation model engineering and LLM-based application development are fundamentally systems engineering disciplines.

If you haven’t yet studied Part 1, we strongly recommend reviewing it first, as it establishes the conceptual foundation essential for understanding the material we’re about to cover.

Read it here:

In this chapter, and the next few, we will cover the fundamental concepts and core building blocks of large language models, analyzing each component and stage in detail.

As always, every notion will be explained through clear examples and walkthroughs to develop a solid understanding.

Let’s begin!

Introduction

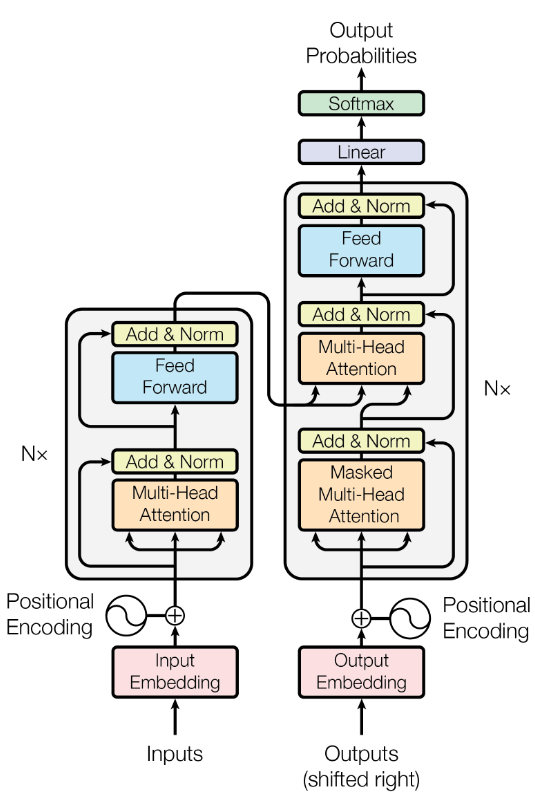

This chapter, and the next few ones, discuss the internal mechanics of large language models.

We will build a strong mental model of the technical fundamentals of LLMs: from how they convert text into numbers and apply attention, to how they are trained and generate text.

By the end of the subsequent set of chapters, you should be comfortable with concepts such as tokenization, embeddings, attention mechanisms, pretraining, and how LLMs generate text using various decoding strategies and parameters.

Additionally, we will discuss the general lifecycle of LLM-based applications, outlining the key stages involved from initial design and development through deployment and ongoing maintenance.

Let’s begin with the very first step in any language model pipeline: converting raw text into numerical representations usable by the model.

Tokenization

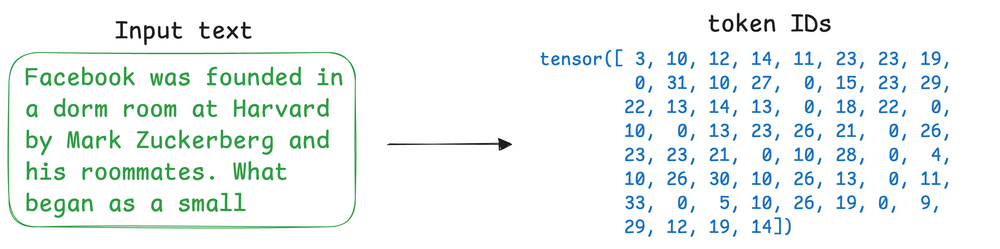

At the heart of an LLM’s input processing is tokenization: breaking text into discrete units called tokens, and assigning each a unique token ID, because before a neural network can process human language, that language must be translated into a format the machine can understand: numerical vectors.

Tokenization is one stage of this two-stage critical translation process, with the other stage being embedding, which maps the tokens into a continuous vector space.

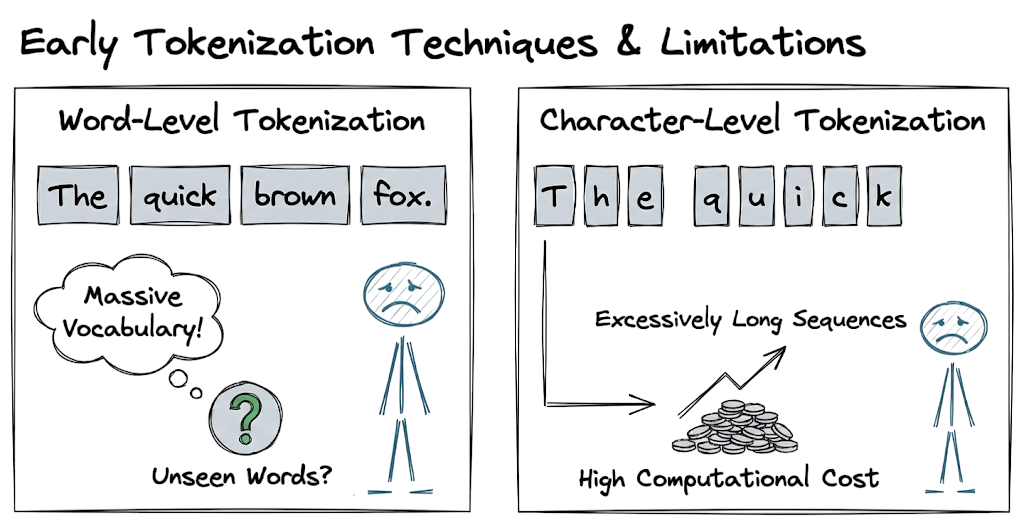

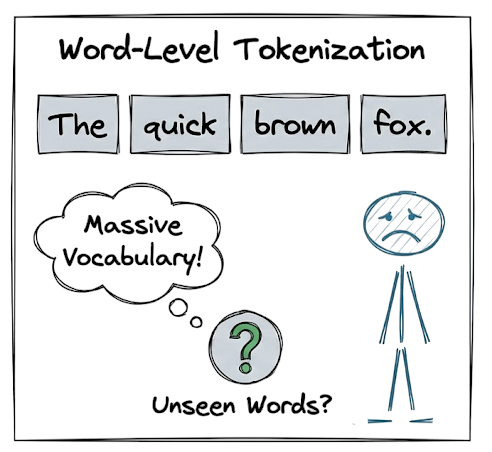

Early techniques relied on word-level tokenization (splitting by spaces) or character-level tokenization. Both approaches have significant limitations.

Word-level tokenization results in massive vocabulary sizes and cannot handle unseen words, while character-level tokenization produces excessively long sequences that dilute semantic meaning and increase computational cost.

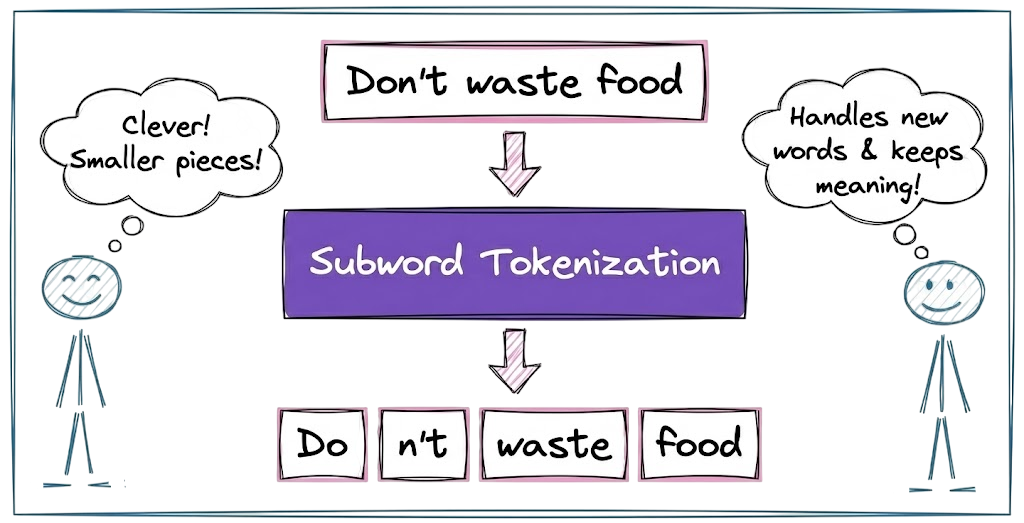

Hence, modern LLMs adopt subword tokenization, which strikes an optimal balance. Here, tokens are often words and subwords, depending on frequency of occurrence. For example, the sentence “Transformers are amazing!” might be tokenized into pieces like ["Transform", "ers", " are", " amazing", "!"].

More formally, the reasons behind using subword units are:

Subwords capture meaning

Unlike single characters, subword tokens can represent meaningful chunks of words. For instance, the word “cooking” can be split into tokens “cook” and “ing”, each carrying part of the meaning.

A purely character-based model would have to learn “cook” vs “cooking” relationships from scratch, whereas subwords provide a head start by preserving linguistic structure.

Vocabulary efficiency

There are far fewer unique subword tokens than full words. Using subword tokens reduces the vocabulary size dramatically compared to word-level tokenizers, which makes the model more efficient to train and use.

For example, instead of needing a vocabulary containing every form of a word (run, runs, running, ran, etc.), a tokenizer might include base tokens like “run” and suffix tokens like “ning” or past tense markers. This keeps the vocabulary (and therefore model size) manageable.

Most LLMs have vocabularies on the order of tens to hundreds of thousands of tokens, far smaller than the number of possible words.

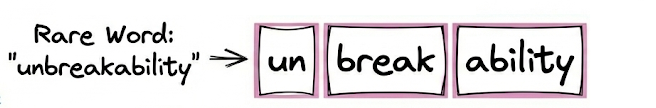

Handling unknown or rare words

Subword tokenization naturally handles out-of-vocabulary words better by breaking them into pieces. If the model encounters a new word it wasn’t trained on, it can split it into familiar segments rather than treating it as an entirely unknown token.

This helps the model generalize to new words by understanding their components.

Now that we understand the basics of subword tokenization, let's take a quick look at the key techniques we use to implement subword tokenization.

Subword tokenization algorithms

The three dominant algorithms in this space are byte-pair encoding (BPE), WordPiece, and Unigram tokenization.

These algorithms build a vocabulary of tokens by starting from characters and iteratively merging common sequences to form longer tokens. The result is a fixed vocabulary where each token may be a word or a frequent subword.

Byte-Pair Encoding (BPE)

Byte-Pair Encoding (BPE) is the standard for models like GPT-2, GPT-3, GPT-4, and the Llama family. It is a frequency-based compression algorithm that iteratively merges the most frequent adjacent pairs of symbols into new tokens.

Mechanism

- Initialization: The vocabulary is initialized with all unique characters in the corpus.

- Statistical Counting: The algorithm scans the corpus and counts the frequency of all adjacent symbol pairs (e.g., "e" followed by "r").

- Merge Operation: The most frequent pair is merged into a new token (e.g., "er"). This new token is added to the vocabulary.

- Iteration: This process repeats until a pre-defined vocabulary size (hyperparameter) is reached.