A Practical Deep Dive Into Memory Optimization for Agentic Systems (Part C)

AI Agents Crash Course—Part 17 (with implementation).

Recap

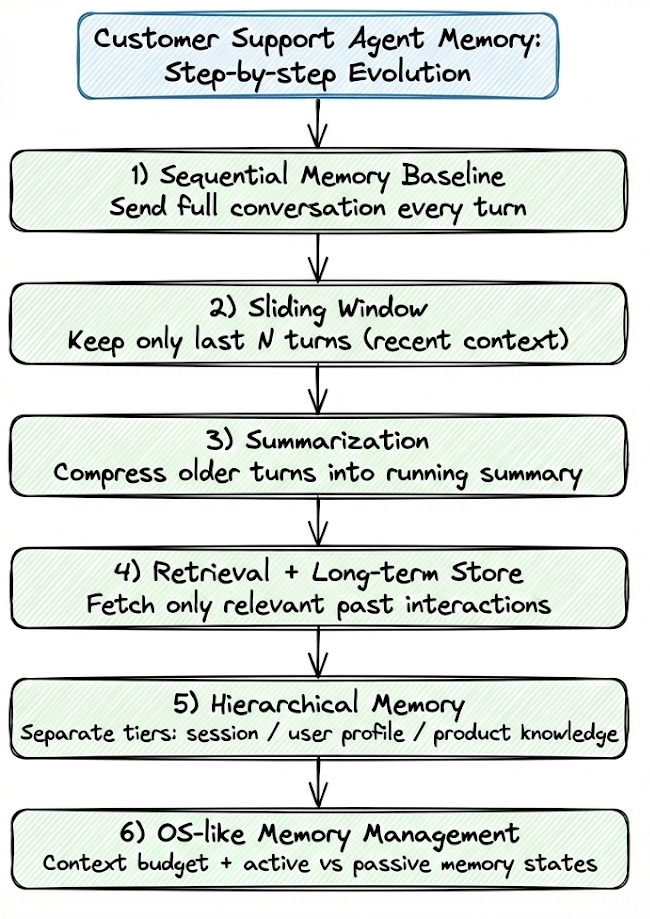

In the previous part (Part 16) of this AI agents crash course, we focused on memory as a first-class design concern for agentic systems.

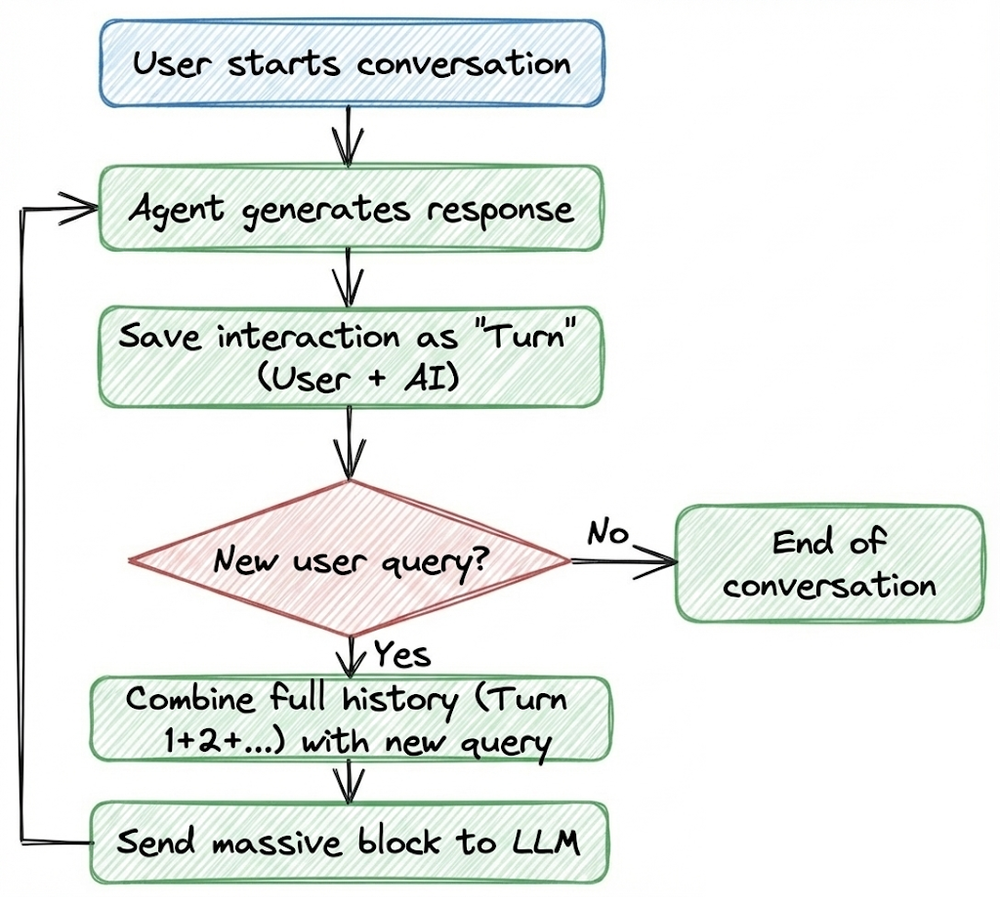

We began by understanding sequential memory, where the entire conversation history is appended and sent to the LLM on every turn.

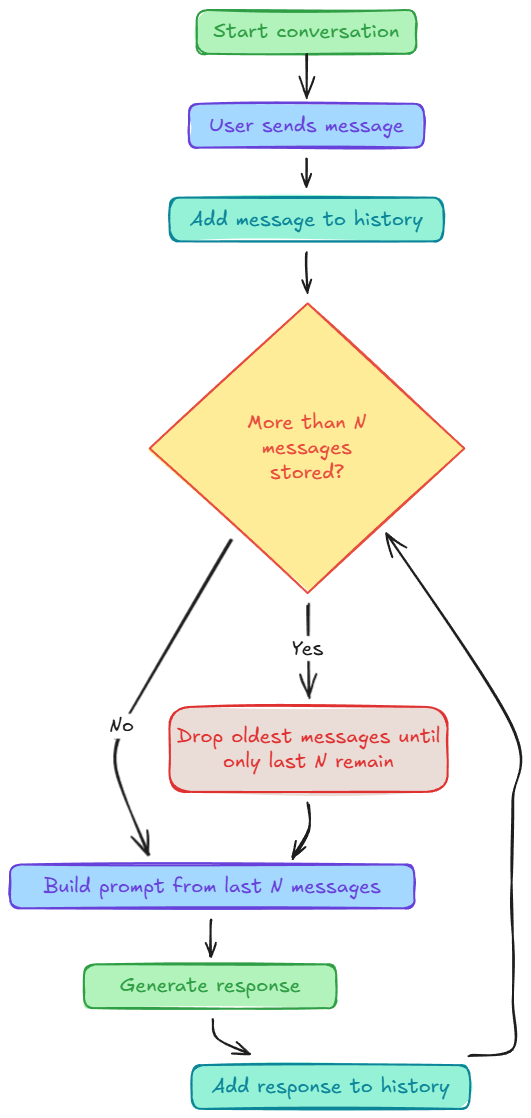

Next, we introduced sliding window memory, which places a hard bound on context size by retaining only the most recent messages. This significantly stabilizes token usage and latency, but at the cost of forgetting older information once it falls outside the window.

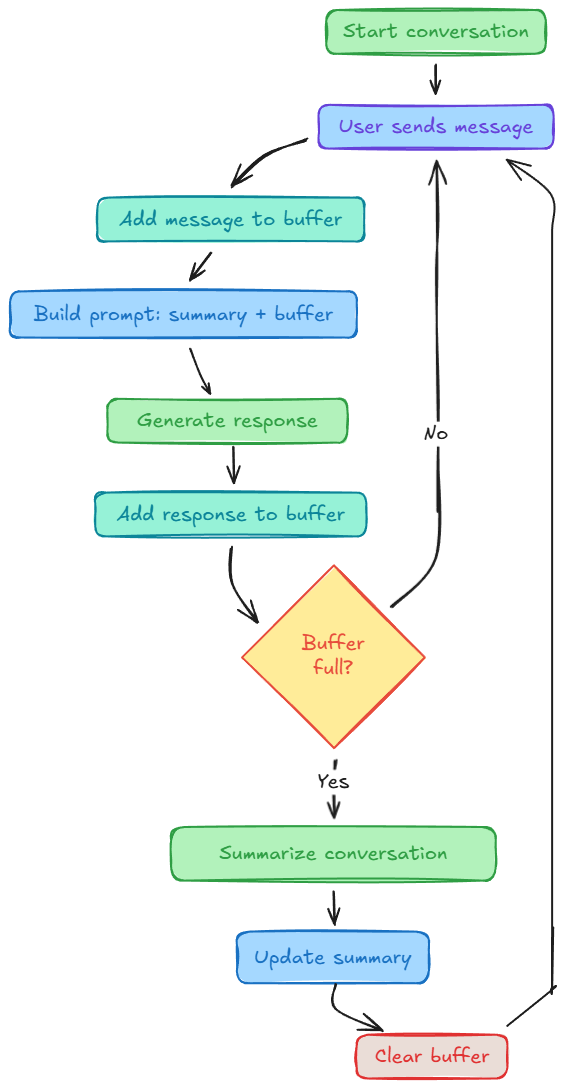

To address this limitation, we moved on to summarization-based memory, where older conversation segments are compressed into a running summary while recent turns remain in full detail.

We then extended this idea further with compression and consolidation, introducing importance-aware memory management.

Throughout the chapter, we grounded every concept in a customer support chatbot example, analyzing how each memory strategy affects behavior, latency, and token consumption in realistic workflows.

If you haven’t gone through the previous chapter yet, we strongly recommend reading it first, as it lays the foundation for the next step in our memory optimization journey.

In this chapter, we will continue our discussion on memory optimization, learning about:

- Retrieval-based memory

- Hierarchical memory

- OS-like memory

Let’s continue.

Retrieval-based memory

So far, all the techniques we discussed so far have been short-term:

- Sequential memory: send the entire conversation so far.

- Sliding window: keep only the last few turns.

- Summarization: compress older parts into a running summary.

All of these live inside a single thread. Once the thread ends, that memory is gone.

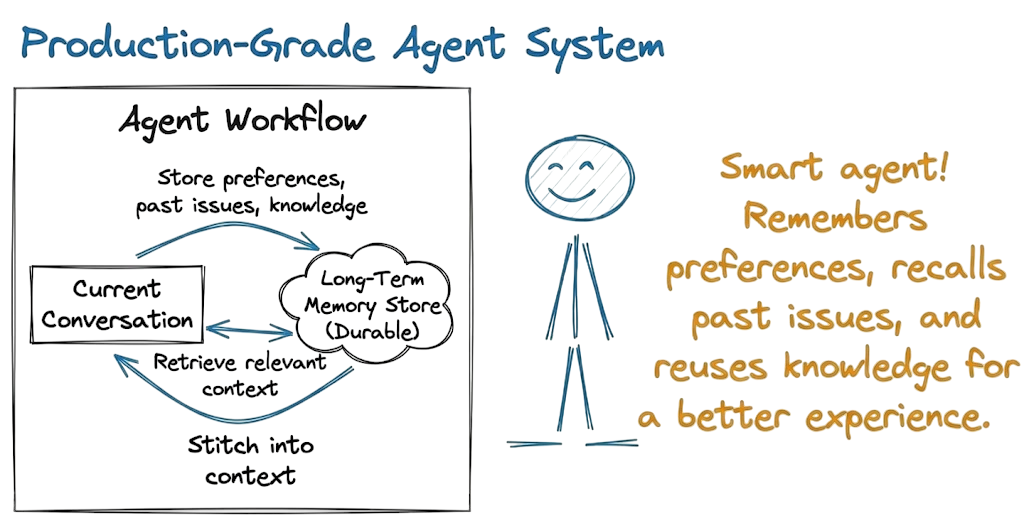

For real, production-grade agentic systems, that’s not enough. You want your agent to:

- remember a user’s preferences across conversations

- recall past issues for the same user/account

- reuse knowledge learned last week in a new session

Instead of keeping everything inside the thread, we need to:

- store durable memory items in a long-term store

- retrieve only the relevant ones for the current query

- stitch them into the context alongside the current conversation

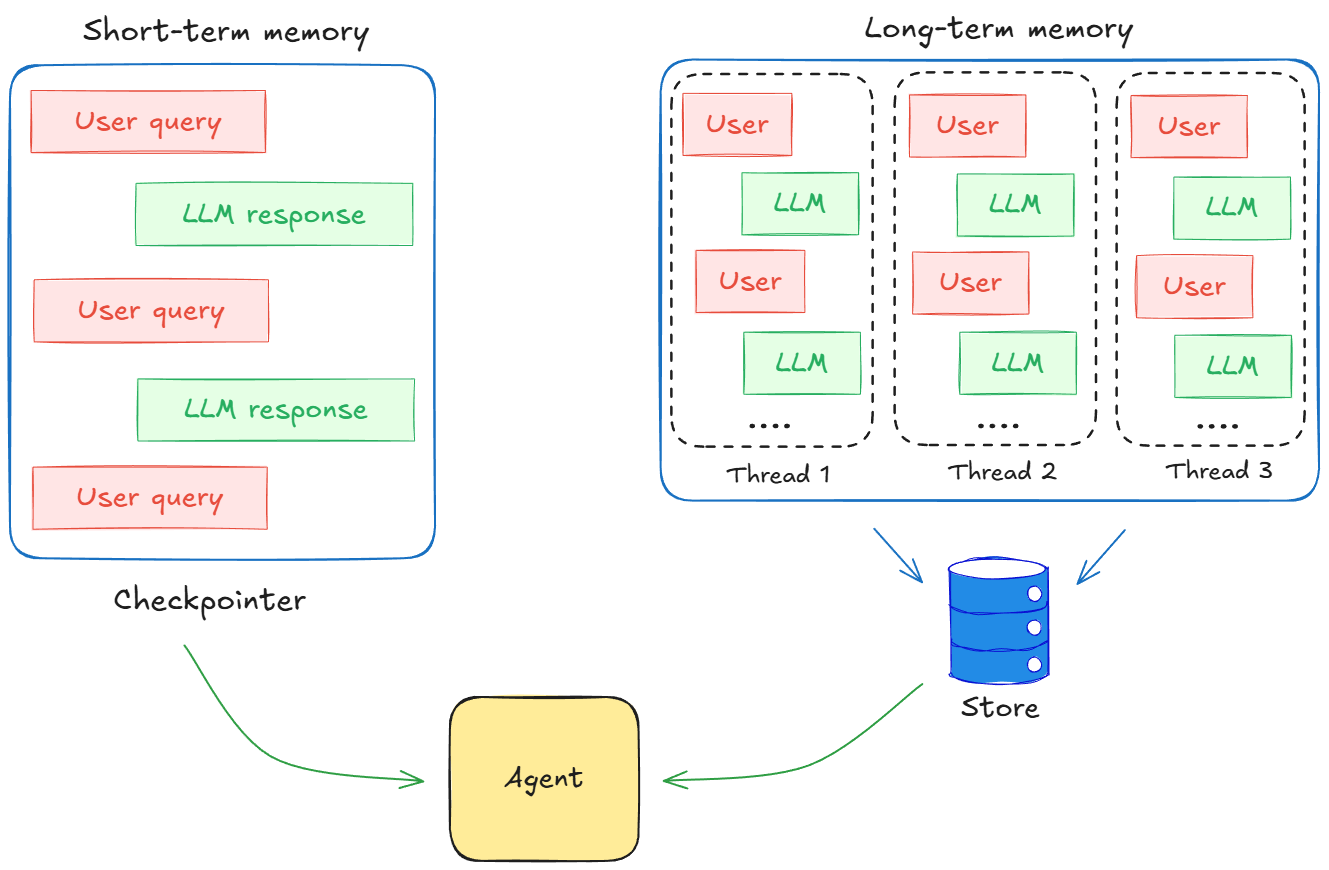

In Part 15, we briefly saw how long-term memory works in LangGraph using the store abstraction.

Here we’ll walk through it step by step, and then wire it into a retrieval-based memory setup for our customer support agent.

Memory store in LangGraph

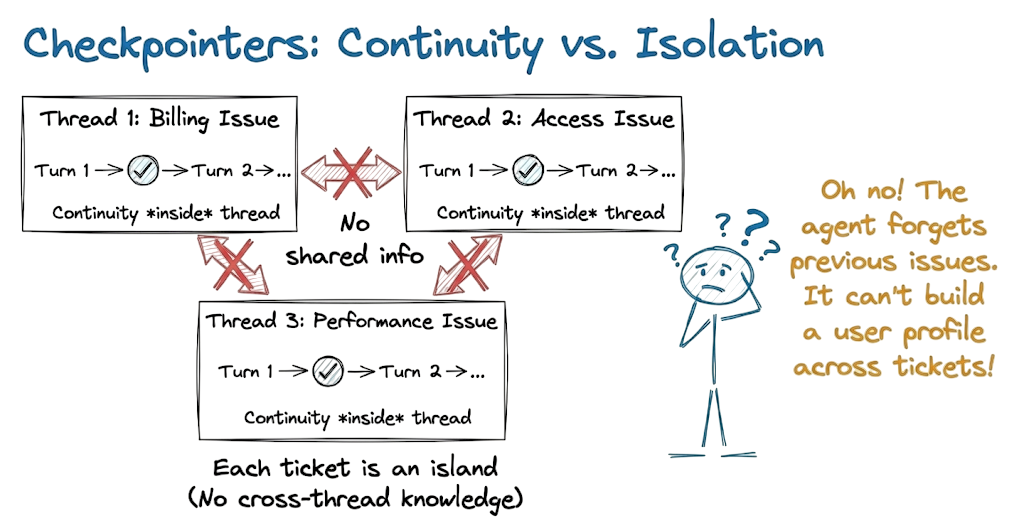

Checkpointers give us continuity inside a thread. As long as we use the same thread ID, LangGraph will restore the previous state and continue the conversation from where you left off.

But checkpointers alone cannot:

- share information between different threads

- carry knowledge across sessions or tickets

- build a persistent profile for a user

Imagine a user who opens three support tickets over a month:

- Ticket 1 – billing issue

- Ticket 2 – access issue

- Ticket 3 – workspace performance issue

With only checkpointers, each ticket is its own island. The agent has no way to reuse what it learned in Ticket 1 when answering Ticket 2 or 3.

This is the exact reason for the need to have stores as an external database that can store important conversations that can be retrieved on demand.

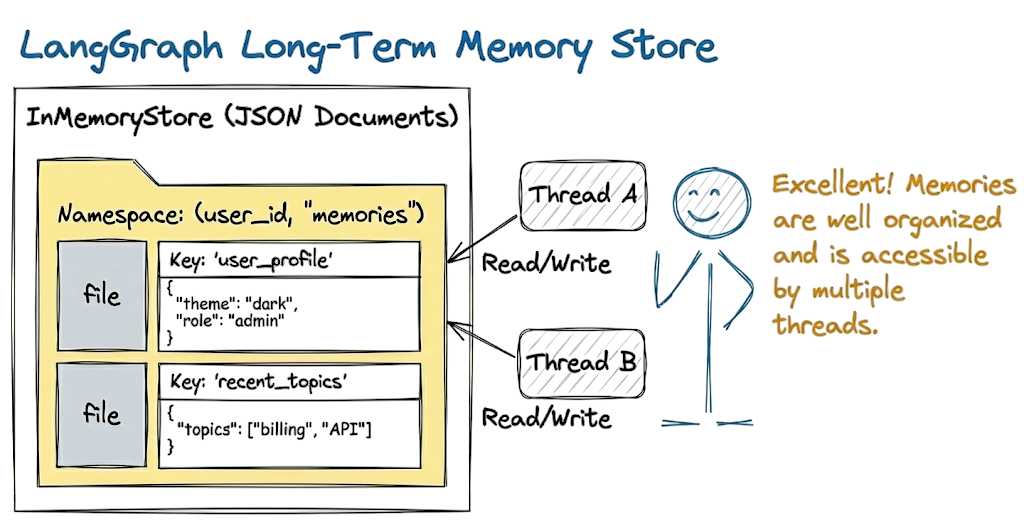

LangGraph stores long-term memories as JSON documents in a store.

Each memory is organized under:

- A namespace is like a folder and is represented as a tuple like

(user_id, "memories"). - A key is like a file name within that folder.

Moreover, you can write and read from the store in any thread. In LangGraph we use the InMemoryStore to implement this.

The good thing about LangGraph is that it takes care of all the backend infrastructure required for the store implementation. We don't need to worry about managing it but it is still useful to understand the basics.

Here’s an implementation of the InMemoryStore:

Here:

InMemoryStorecreates a store which is essentially just a dictionary in memory.- Memories are grouped by a namespace, which is a tuple of strings.

We use (user_id, "memories") here, but you could just as well use (project_id, "docs") or (team_id, "preferences") whatever suits your use case.

To save a memory, we use the put method:

In this snippet:

memory_idis a unique key inside this namespace.memoryis any JSON-serializable document such as a simple dictionary.putstores this(key, value)pair under the given namespace.

To read memories back, we use the search method:

Each memory item returned by search is an Item class with:

value: the memory or user preference savedkey: the unique key used (memory_id)namespace: the namespace for this memorycreated_at/updated_at: timestamps

That’s the core concept:

put(namespace, key, value)to save a memorysearch(namespace, ...)to retrieve a memory

So far, search returns all items for a namespace and follows a simple retrieval strategy based on traditional keyword search. This doesn’t scale well if you have hundreds or thousands of memories per user.

In real systems, we want semantic retrieval that first converts text into vector embeddings and store these embeddings in an index. At query time, we embed the query and find the closest memories using a similarity metric.

Let us first configure our embedding model before going to the implementation part. We will again be using OpenRouter for this.

InMemoryStore can be configured with an embedding index like this:

Here:

embedis an embedding function (OpenAI embeddings).dimsis the dimensionality of the embedded vectors.fieldstells the store which fields of our values to embed."food_preference"will embed the value of this key in the dict (i.e. I like pizza)."$"is a catch-all for the entire object.

Now, when we put memories into the store, vectors are computed and stored behind the scenes. We can then issue semantic queries:

Here:

queryis a natural language search string.limitcontrols how many top matches you want.- The store embeds the query, computes similarity with stored embeddings, and returns the best matches.

We can also control which parts of the memories get embedded by configuring the fields parameter or by specifying the index parameter when storing memories:

This is the core of retrieval-based memory systems:

- define what you save

- define how it is embedded

- ask semantic questions and get back relevant chunks of memory

Before we start to implement this strategy for our support agent it is important to note that the InMemoryStore is prefect for local experiments, unit tests and small prototypes but not enough for a production-grade app.

For production workloads, we almost always want a robust vector database backend that can handle millions of memory items, is scalable with efficient read/write operations and supports low-latency search and retrieval.

Implementation

Now that the store and semantic search pieces are clear, we can design a retrieval-based memory layer for our customer support agent.

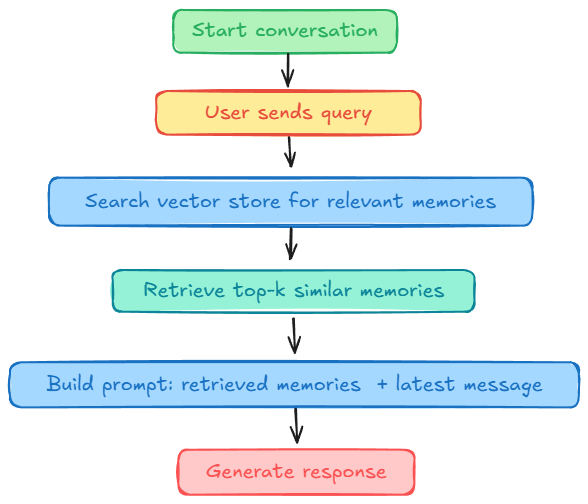

Here's the workflow:

- We add important long-term facts about a user into the store (plan, workspace names, previous issues, etc.).

- When the user opens a new ticket and asks a question, the agent:

- looks up these long-term memories via semantic search

- injects the relevant ones into the prompt

- answers using both the current conversation and the retrieved context

We’ll keep the design simple and focused on retrieval. Let's define our state: