Context Engineering: Prompt Management, Defense, and Control

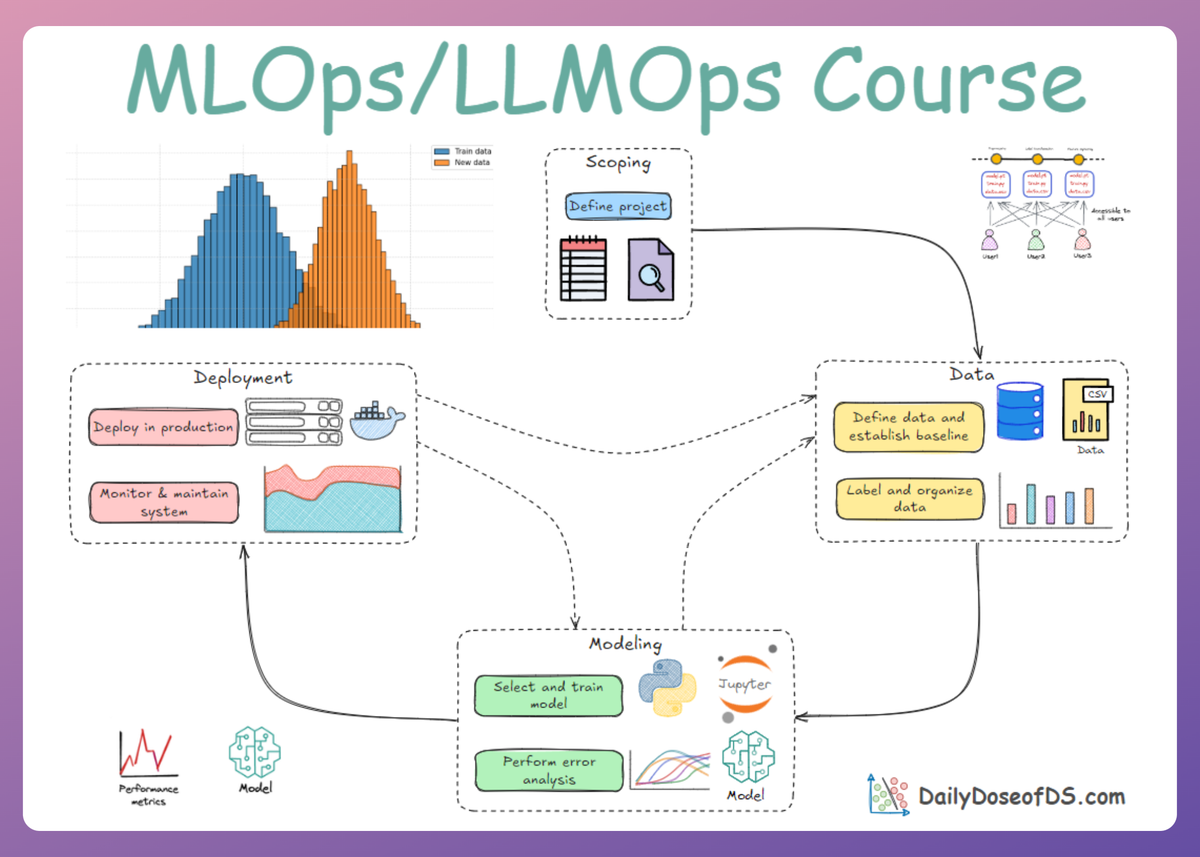

LLMOps Part 6: Exploring prompt versioning, defensive prompting, and techniques such as verbalized sampling, role prompting and more.

Recap

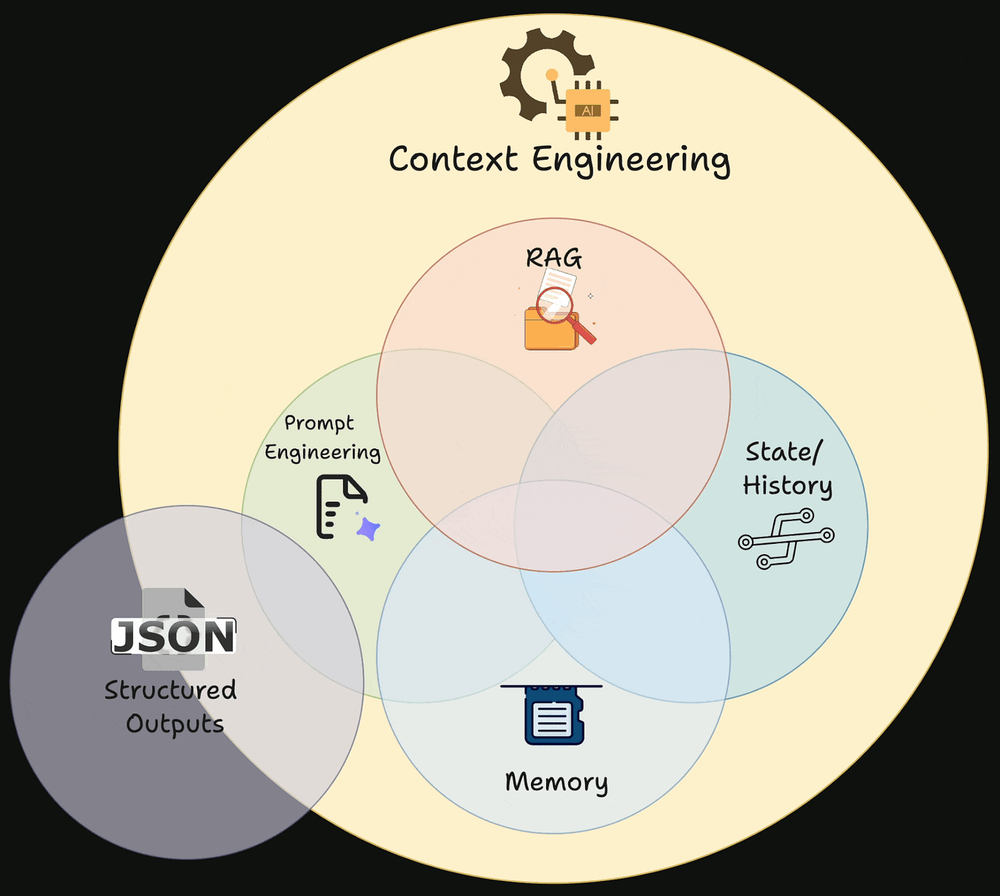

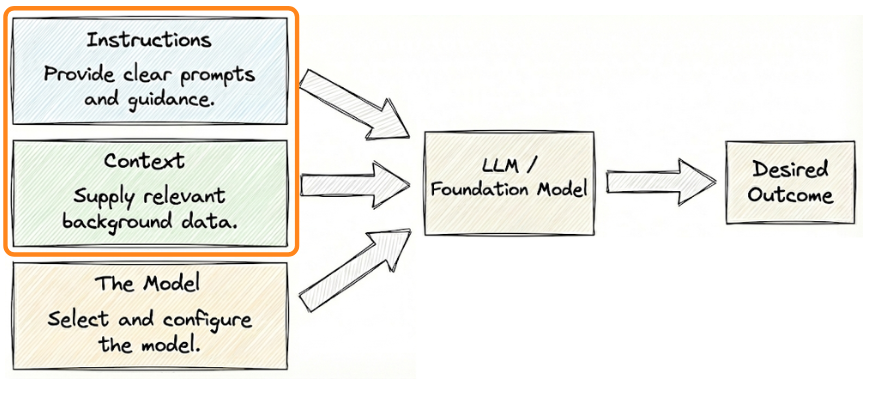

In the previous chapter (part 5), we laid the foundations of prompt engineering, a subset of context engineering.

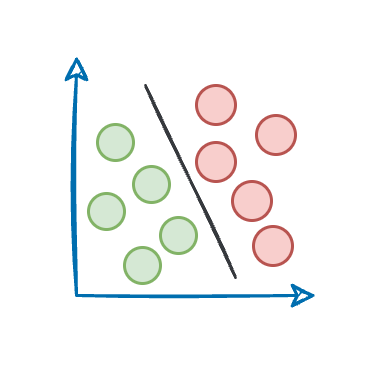

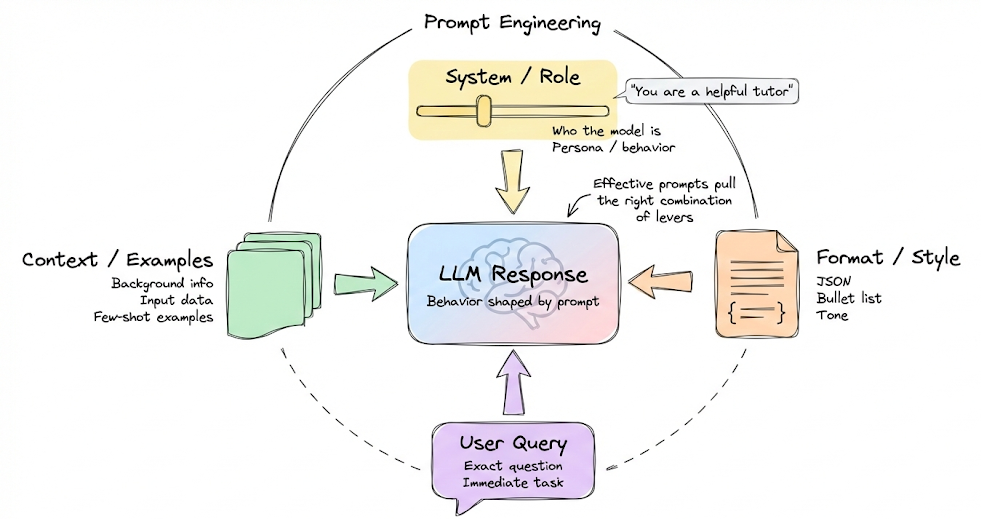

We started by building a basic understanding of prompt engineering and context engineering, and explained why prompts are best viewed as control surfaces that shape model behavior probabilistically.

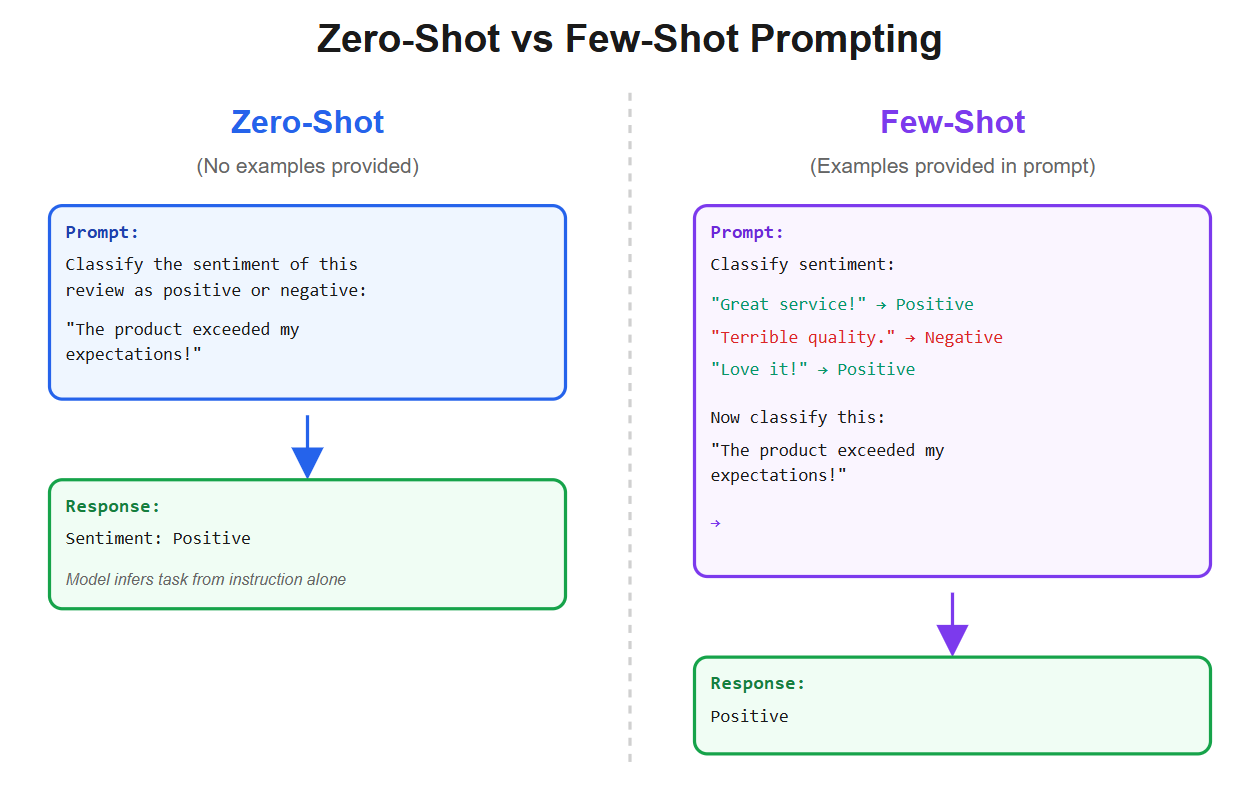

We then grounded this idea with the fundamentals of in-context learning, showing how zero-shot and few-shot prompting work.

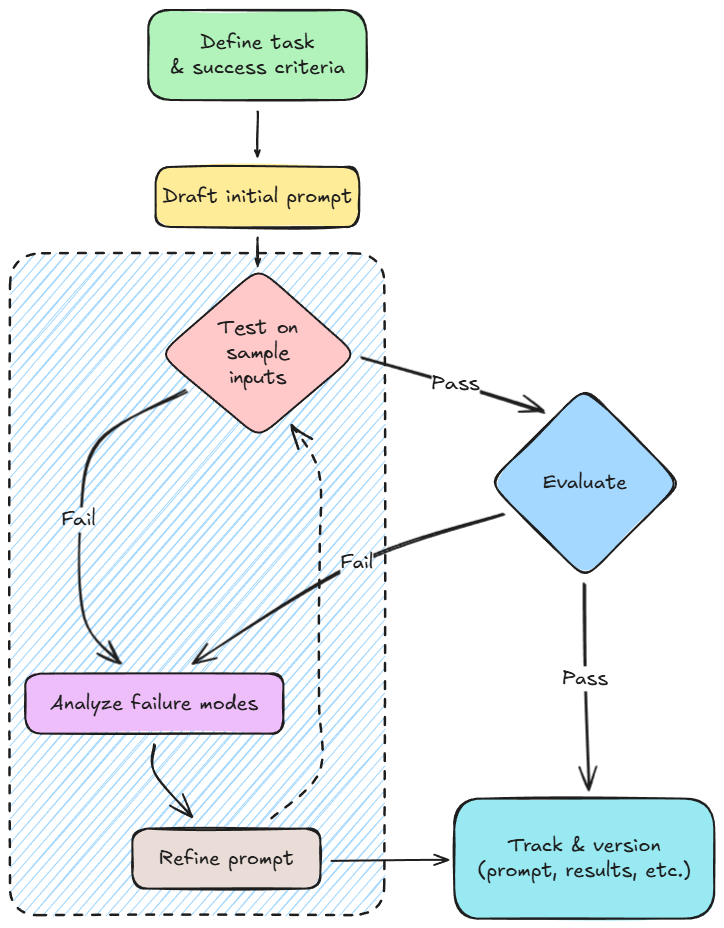

Next, we introduced a systematic prompt development workflow. This framed prompting similar to software development: specification, debugging, evaluation, and versioning.

From there, we covered the major prompt types used in real applications: system prompts, user prompts, few-shot examples, instruction + context prompts, and formatting prompts.

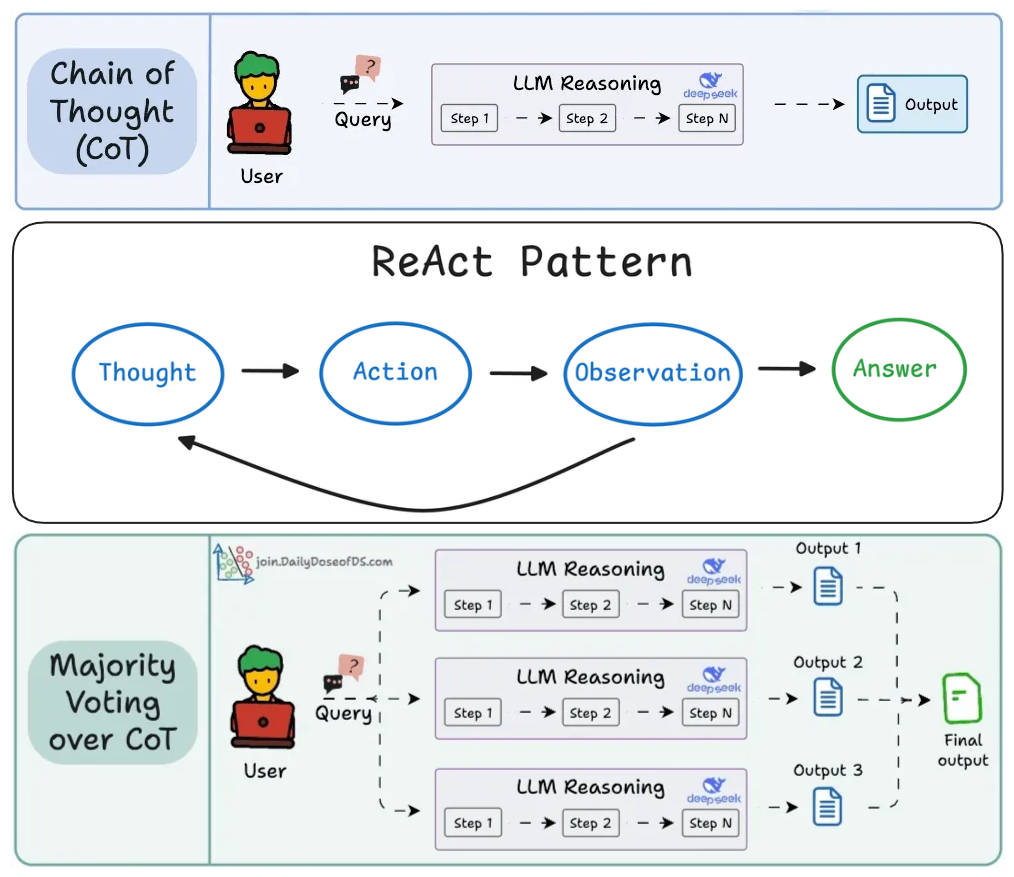

We then moved beyond basics into widely used prompting techniques: chain-of-thought prompting, ReAct as a reasoning-and-tool-use control loop, and self-consistency as an “ensemble at inference time” to improve reliability when correctness matters.

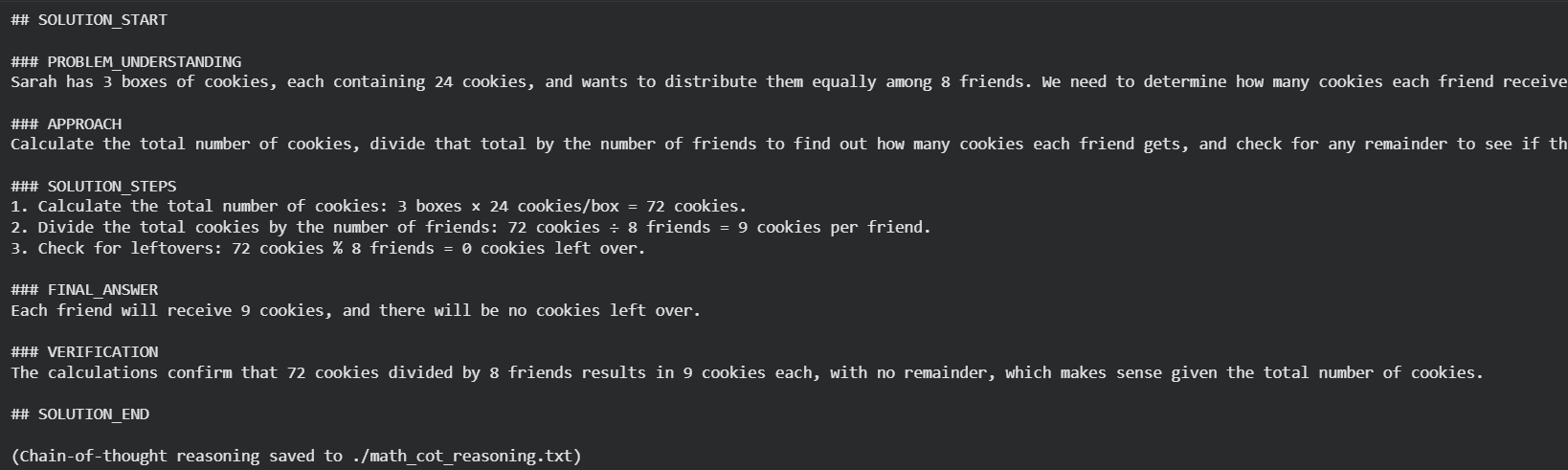

Finally, we tied the concepts together with a hands-on implementation: a small math-solver pipeline that combines system instructions, strict formatting, chain-of-thought, and demonstrates a pattern where reasoning is logged for audits while only the clean final answer is shown to the user.

By the end of the chapter, we had a clear mental model of how prompts influence model behavior, how to iterate on prompts, and how advanced prompting patterns trade simplicity for capability.

If you haven’t yet gone through Part 5, we strongly recommend reviewing it first, as it lays the conceptual groundwork for everything that follows.

Read it here:

In this chapter, we will be going deeper into prompt versioning, defensive prompting, and techniques like verbalized sampling, role prompting and more.

As always, every notion will be explained through clear examples and walkthroughs to develop a solid understanding.

Let’s begin!

Prompt versioning

Prompt versioning means treating each prompt as a versioned artifact with a clear history and explicit relationships to how the system behaves. In production environments, prompts are as critical as code and configuration.

Small changes in wording, structure, or constraints can significantly alter model outputs, sometimes in non-obvious ways.

Without proper versioning, we lose traceability, rollback capability, reproducibility, and the ability to govern or reason about prompt-driven behavior. Debugging becomes guesswork, and even minor prompt tweaks can silently introduce regressions.

A production-ready approach to prompt versioning follows a set of core principles as discussed below:

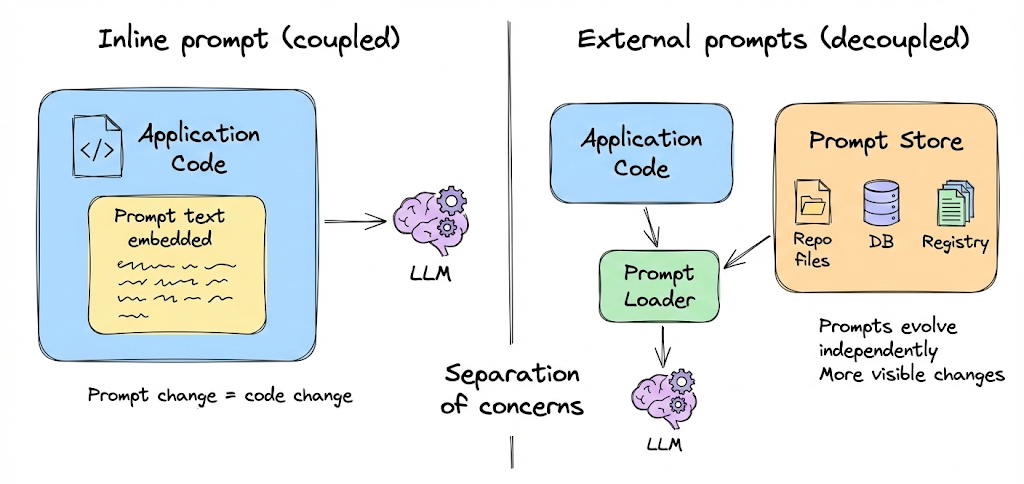

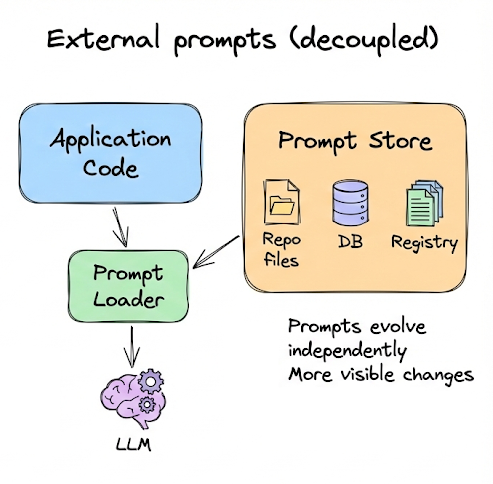

Separate prompts from application code

Prompts should not live inline inside application logic. Embedding prompt text directly in functions or API calls tightly couples behavior changes to code deploys.

Instead, prompts should be stored externally, for example as files in a repository, entries in a database, or records in a registry.

This separation of concerns allows prompts to evolve independently of code, reduces the risk of unintended rollouts, and makes prompt changes more visible and auditable.

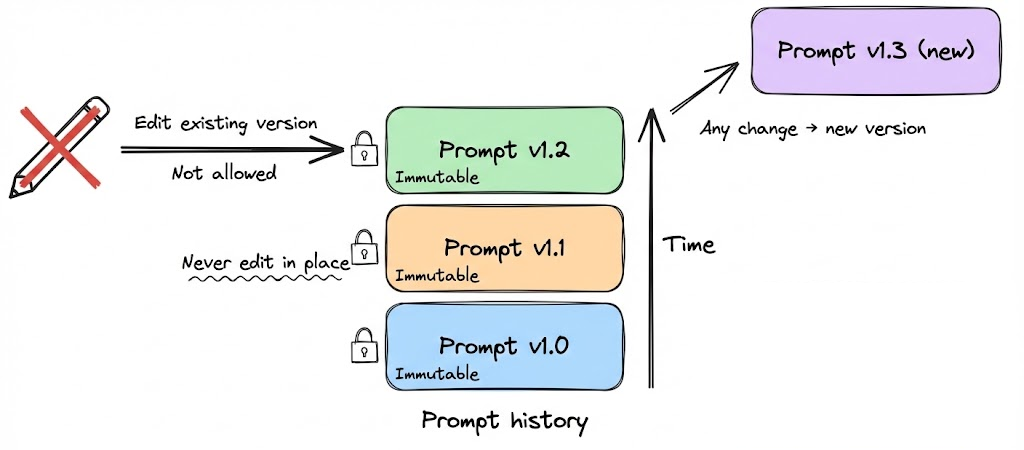

Immutable prompt versions

Each prompt version should be immutable. Once a version is created, it must never be edited in place.

If a prompt needs to change, even slightly, a new version should be created. This mirrors how release artifacts are handled in mature software systems. Any reference to a version identifier must always resolve to the same prompt text and context.

Immutability is what makes logs, evaluations, audits, and incident investigations trustworthy. Without it, historical behavior cannot be reliably reconstructed.

Clear and systematic versioning

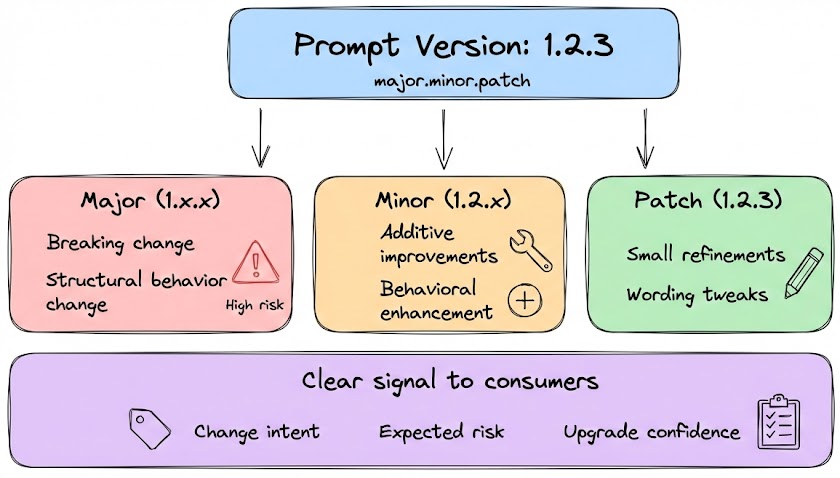

Prompt versions should follow a consistent and explicit versioning scheme. Many teams adopt semantic versioning using a three-part identifier such as major.minor.patch like 1.0.0 where:

- A major version indicates a breaking or structural change in prompt behavior.

- A minor version reflects additive or behavioral improvements.

- A patch version captures small refinements or wording tweaks.

This structure communicates intent and risk to anyone consuming the prompt and aligns prompt evolution with established engineering conventions.

Metadata and context tracking

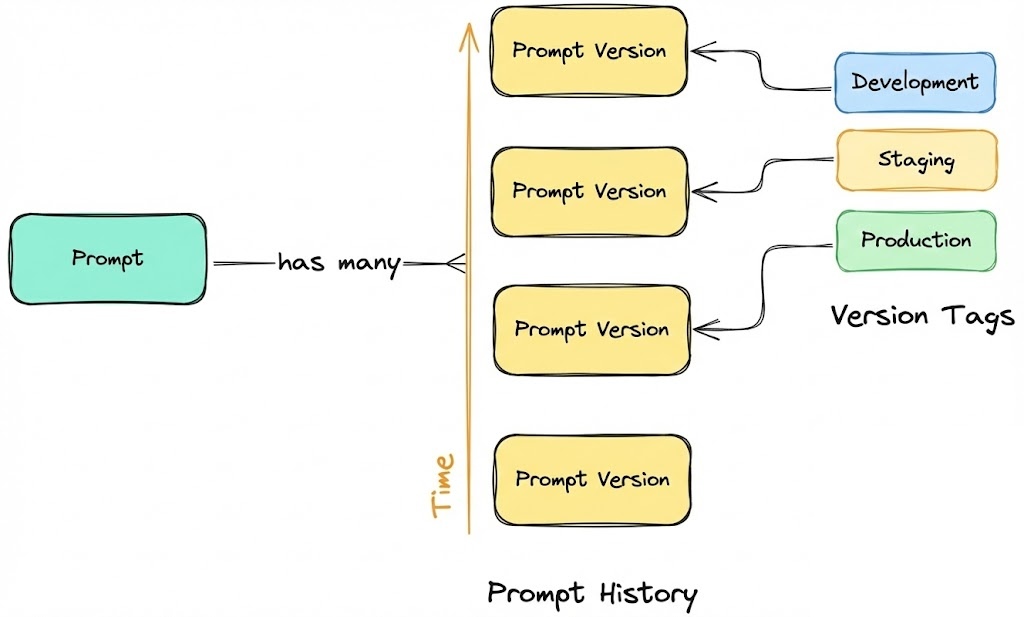

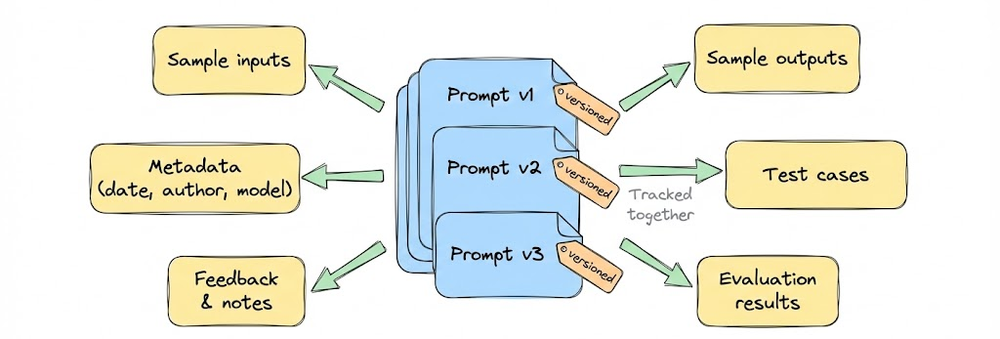

Versioning is not just about storing text. Each prompt version should carry metadata that explains its purpose and provenance.

At minimum, metadata should include who created or modified the prompt, when it was changed, target model and parameters.

In more mature systems where large teams needs to collaborate, this can expand to include linked evaluation results, supported use cases, and environment tags such as development, staging, or production.

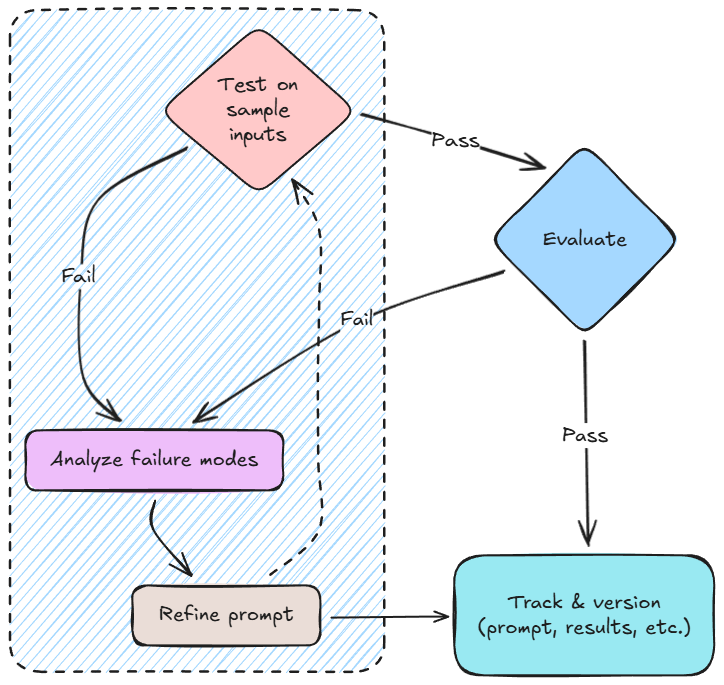

Testing and evaluation as a gate

Prompt changes and versions should be evaluated using consistent testing.

Evaluation may include automated test sets, task-specific metrics, failure analysis, or structured human review. Results should be recorded and used as promotion gates.

Regression handling and rollback

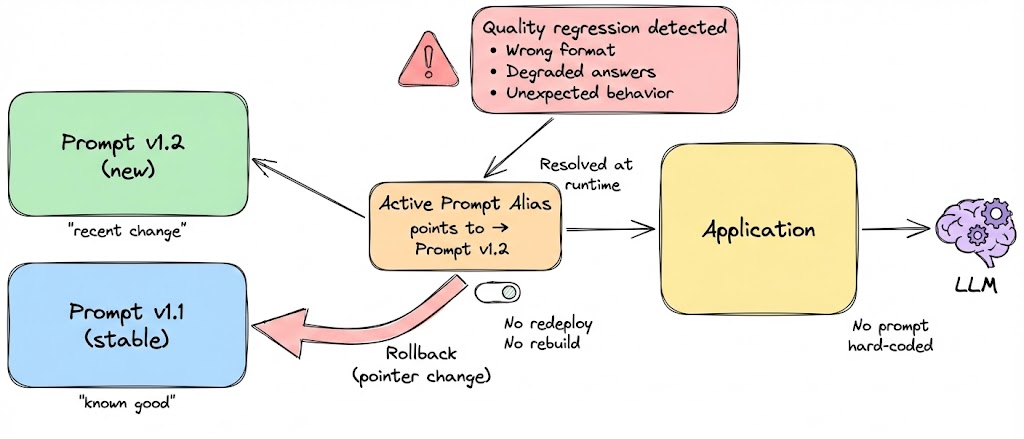

Because LLM outputs are probabilistic, even small prompt changes can introduce unexpected regressions. For this reason, prompt updates must be treated as runtime configuration changes, not code changes. This is another reason why decoupling of prompts from application logic is important.

A robust prompt versioning strategy includes an immediate rollback mechanism. If a new prompt version causes degraded quality, incorrect behavior, or format violations, we should be able to switch back to the last known stable prompt at runtime, without redeploying the application or rebuilding infrastructure.

This is typically achieved by resolving the “active” prompt version dynamically (for example, via an alias) rather than hard-coding a specific version in the application. Rolling back then becomes a simple pointer change, similar to reverting a feature flag.

Prompt regressions should be handled with the same rigor as code regressions: monitored, quickly reversible, and isolated from deployment cycles.

To summarize: prompt versioning in production is fundamentally about explicit management. Prompts should be stored separately from code, versioned immutably, enriched with metadata, evaluated systematically, deployed through controlled aliases and monitored in operation. When treated this way, prompts evolve predictably, just like any other core component in a well-engineered production system.

With this, we have covered the key concepts of prompt versioning and will explore them further in the hands-on section of this chapter. Let us now move on to another core topic: prompt templates and their role in prompt management.

Prompt templates

Most real-world LLM applications need to format prompts dynamically: inserting user input or contextual data into the prompt. Hardcoding a single static prompt is rarely enough.

This is where prompt templates come in. A prompt template is essentially a string with placeholders that get filled in at runtime. Managing these templates well is important for clarity and consistency.

You can use simple string formatting or more sophisticated template engines to manage prompts. For instance, consider the simple template below:

Here {itinerary_details} is a placeholder for data that will be plugged in (e.g., the user’s flight info). By using a template, you ensure the structure and wording of the prompt remain consistent every time, and only the variable parts change. This reduces human error.

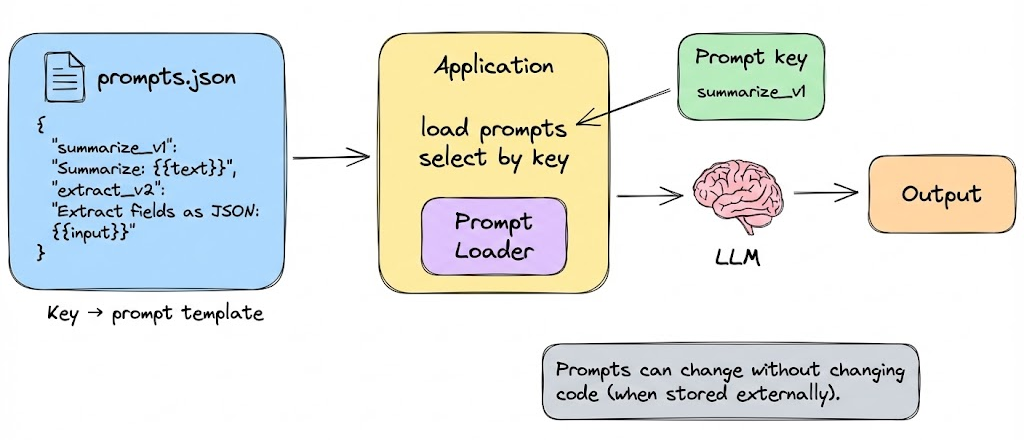

Organizing templates in code or config files is also useful. For example, you might have a YAML or JSON file that stores prompts with keys, and your application loads them.

This ties back to prompt versioning, templates can be versioned just like full prompts. In fact templates are the prompts that are mostly in use and talked about for AI applications.

However, with templates, there are two very important things that we must keep in mind: