Tools, Resources and Prompts

Tools, prompts and resources form the three core capabilities of the MCP framework. Capabilities are essentially the features or functions that the server makes available.

- Tools: Executable actions or functions that the AI (host/client) can invoke (often with side effects or external API calls).

- Resources: Read-only data sources that the AI (host/client) can query for information (no side effects, just retrieval).

- Prompts: Predefined prompt templates or workflows that the server can supply.

Tools

Tools are what they sound like: functions that do something on behalf of the AI model. These are typically operations that can have effects or require computation beyond the AI’s own capabilities.

Importantly, Tools are usually triggered by the AI model’s choice, which means the LLM (via the host) decides to call a tool when it determines it needs that functionality.

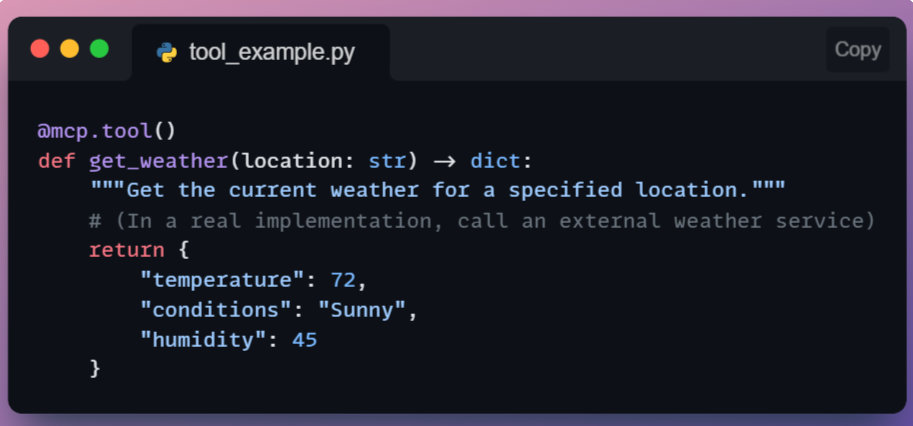

Suppose we have a simple tool for weather. In an MCP server’s code, it might look like:

This Python function, registered with @mcp.tool(), can be invoked by the AI via MCP.

When the AI calls tools/call with name "get_weather" and {"location": "San Francisco"} as arguments, the server will execute get_weather("San Francisco") and return the dictionary result.

The client will get that JSON result and make it available to the AI. Notice the tool returns structured data (temperature, conditions), and the AI can then use or verbalize (generate a response) that info.

Since tools can do things like file I/O or network calls, an MCP implementation often requires that the user permit a tool call.

For example, Claude’s client might pop up “The AI wants to use the ‘get_weather’ tool, allow yes/no?” the first time, to avoid abuse. This ensures the human stays in control of powerful actions.

Tools are analogous to “functions” in classic function calling, but under MCP, they are used in a more flexible, dynamic context. They are model-controlled but developer/governance-approved in execution.

Resources

Resources provide read-only data to the AI model.

These are like databases or knowledge bases that the AI can query to get information, but not modify.

Unlike tools, resources typically do not involve heavy computation or side effects, since they are often just information lookup.

Another key difference is that resources are usually accessed under the host application’s control (not spontaneously by the model). In practice, this might mean the Host knows when to fetch a certain context for the model.

For instance, if a user says, “Use the company handbook to answer my question,” the Host might call a resource that retrieves relevant handbook sections and feeds them to the model.

Resources could include a local file’s contents, a snippet from a knowledge base or documentation, a database query result (read-only), or any static data like configuration info.

Essentially, anything the AI might need to know as context. An AI research assistant could have resources like “ArXiv papers database,” where it can retrieve an abstract or reference when asked.

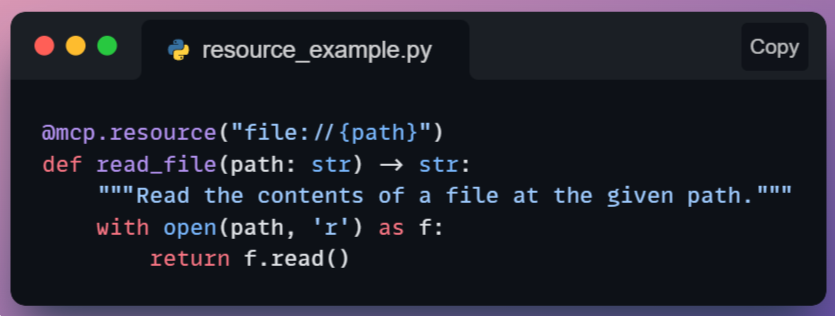

A simple resource could be a function to read a file:

Here we use a decorator @mcp.resource("file://{path}") which might indicate a template for resource URIs.

The AI (or Host) could ask the server for resources.get with a URI like file://home/user/notes.txt, and the server would callread_file("/home/user/notes.txt") and return the text.

Notice that resources are usually identified by some identifier (like a URI or name) rather than being free-form functions.

They are also often application-controlled, meaning the app decides when to retrieve them (to avoid the model just reading everything arbitrarily).

From a safety standpoint, since resources are read-only, they are less dangerous, but still, one must consider privacy and permissions (the AI shouldn’t read files it’s not supposed to).

The Host can regulate which resource URIs it allows the AI to access, or the server might restrict access to certain data.

In summary, Resources give the AI knowledge without handing over the keys to change anything.

They’re the MCP equivalent of giving the model reference material when needed, which acts like a smarter, on-demand retrieval system integrated through the protocol.

Prompts

Prompts in the MCP context are a special concept: they are predefined prompt templates or conversation flows that can be injected to guide the AI’s behavior.

Essentially, a Prompt capability provides a canned set of instructions or an example dialogue that can help steer the model for certain tasks.

But why have prompts as a capability?

Think of recurring patterns: e.g., a prompt that sets up the system role as “You are a code reviewer,” and the user’s code is inserted for analysis.

Rather than hardcoding that in the host application, the MCP server can supply it.

Prompts can also represent multi-turn workflows.

For instance, a prompt might define how to conduct a step-by-step diagnostic interview with a user. By exposing this via MCP, any client can retrieve and use these sophisticated prompts on demand.

As far as control is concerned, Prompts are usually user-controlled or developer-controlled.

The user might pick a prompt/template from a UI (e.g., “Summarize this document” template), which the host then fetches from the server.

The model doesn’t spontaneously decide to use prompts the way it does tools.

Rather, the prompt sets the stage before the model starts generating. In that sense, prompts are often fetched at the beginning of an interaction or when the user chooses a specific “mode”.

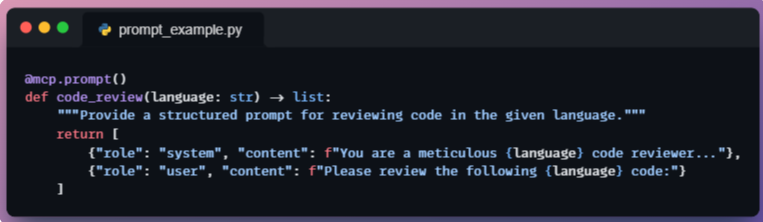

Suppose we have a prompt template for code review. The MCP server might have:

This prompt function returns a list of message objects (in OpenAI format) that set up a code review scenario.

When the host invokes this prompt, it gets those messages and can insert the actual code to be reviewed into the user content.

Then it provides these messages to the model before the model’s own answer. Essentially, the server is helping to structure the conversation.

While we have personally not seen much applicability of this yet, common use cases for prompt capabilities include things like “brainstorming guide,” “step-by-step problem solver template,” or domain-specific system roles.

By having them on the server, they can be updated or improved without changing the client app, and different servers can offer different specialized prompts.

An important point to note here is that prompts, as a capability, blur the line between data and instructions.

They represent best practices or predefined strategies for the AI to use.

In a way, MCP prompts are similar to how ChatGPT plugins can suggest how to format a query, but here it’s standardized and discoverable via the protocol.