Foundations of AI Engineering and LLMs

LLMOps Part 1: An overview of AI engineering and LLMOps, and the core dimensions that define modern AI systems.

Introduction

So, while learning MLOps, we explored traditional machine learning models and systems.

We learned how to take them from experimentation to production using the principles of MLOps.

Now, a new question emerges:

What happens when the “model” is no longer a custom-trained classifier, but a massive foundation model like Llama, GPT, or Claude?

Are the same principles enough?

Not quite.

Modern AI applications are increasingly powered by large language models (LLMs), which are systems that can generate text, reason over documents, call tools, write code, analyze data, and even act as autonomous agents.

These models introduce an entirely new set of engineering challenges that traditional MLOps does not fully address.

This is where AI engineering and LLMOps come in.

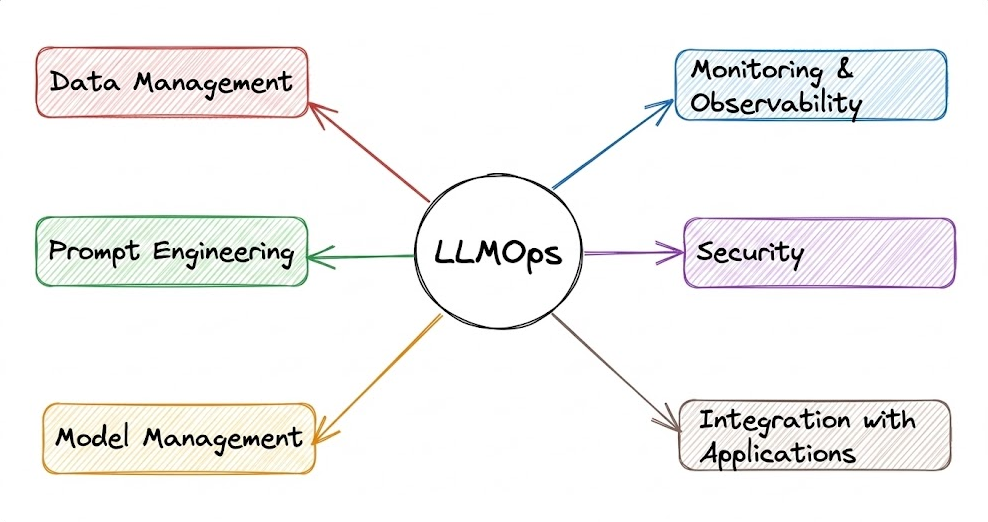

AI engineering, and specifically LLMOps (Large Language Model Operations), are the specialized practices for managing and maintaining LLMs and LLM-based applications in production, ensuring they remain reliable, accurate, secure, and cost-effective.

LLMOps aims to manage language models and the applications built on them by drawing inspiration from MLOps. It applies reliable software engineering and DevOps practices to LLM-based systems, ensuring that all components work together seamlessly to deliver value.

Now that we are starting the LLMOps phase of our MLOps and LLMOps crash course, the aim is to provide you with a thorough explanation and systems-level thinking to build AI applications for production settings.

Just as in the MLOps phase, each chapter will clearly explain necessary concepts, provide examples, diagrams, and implementations.

As we progress, we will see how we can develop the critical thinking required for taking our applications to the next stage and what exactly the framework should be for that.

We’ll begin with the fundamentals of AI engineering and LLMOps, incorporate related concepts, and progressively deepen our understanding with each chapter.

As for this part, we will focus on laying the foundation by exploring what LLMOps is, why it matters, and how it shapes the development of modern AI systems.

Let's begin!

Fundamentals of AI engineering & LLMs

Large language models (LLMs) and foundation models, in general, are reshaping the way modern AI systems are built.

Out of this, AI engineering has emerged as a distinct discipline, one that focuses on building practical applications powered by AI models (especially large pre-trained models).

It evolved out of traditional machine learning engineering as companies moved from training bespoke ML models to harnessing powerful foundation models developed by others.

In essence, AI engineering blends software engineering, data engineering, and ML to develop, deploy, and maintain AI-driven systems that are reliable and scalable in real-world conditions.

At first glance, an “AI Engineer” might sound like a rebranding of an ML engineer, and indeed, there is significant overlap, but there are important distinctions.

AI engineering emphasizes using and adapting existing models (like open-source LLMs or API models) to solve problems, whereas classical ML engineering often centers on training models from scratch on curated data.

AI engineering also deals with the engineering challenges of integrating AI into products: handling data pipelines, model serving infrastructure, continuous evaluation, and iteration based on user feedback.

The role sits at the intersection of software development and machine learning, requiring knowledge of both deploying software systems and understanding AI model behavior.

The AI application stack

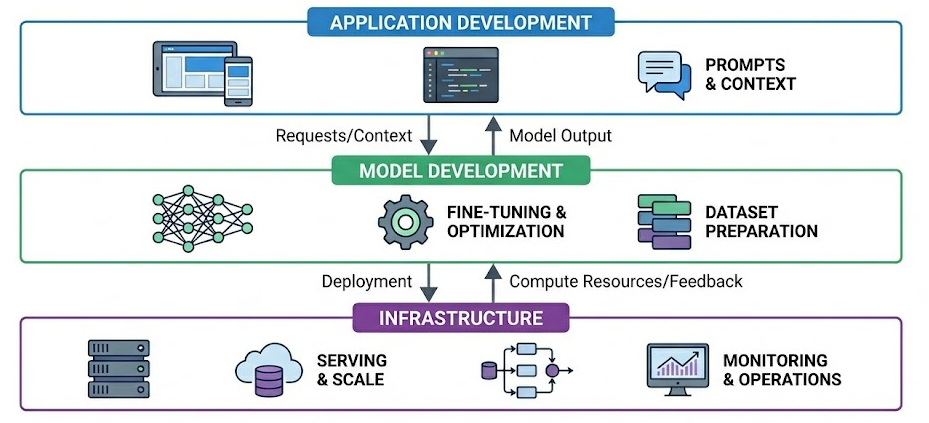

AI engineering can be thought of in terms of a layered stack of responsibilities, much like traditional software systems. At a high level, any AI-driven application involves three layers:

- The application itself (user interface and logic integrating AI)

- The model or model development layer

- The infrastructure layer that supports serving and operations

Application development (top layer)

At this layer, engineers build the features and interfaces that end-users interact with, powered by AI under the hood.

With powerful models readily available via libraries or APIs, much of the work here involves prompting the model effectively and supplying any additional context the model needs.

Because the model’s outputs directly affect user experience, rigorous evaluation is crucial at this layer. AI engineers must also design intuitive interfaces and handle product considerations (for example, how users provide input to the LLM and how the AI responses are presented).

This layer has seen explosive growth in the last couple of years, as it’s easier than ever to plug an existing model into an app or workflow.

Model development (middle layer)

This layer is traditionally the domain of ML engineers and researchers. It includes choosing model architectures, training models on data, fine-tuning pre-trained models, and optimizing models for efficiency.

When working with foundation models, model development typically involves adapting an existing pretrained model rather than training one from scratch. It can involve tasks like fine-tuning an LLM on domain-specific data and performing optimization (e.g., quantizing or compressing).

Data is a central piece here: preparing datasets for fine-tuning or evaluating models, which might include labeling data or filtering and augmenting existing corpora.

Hence, even though foundation models are used as a starting point, understanding how models learn (e.g., knowledge of training algorithms, loss functions, etc.) remains valuable in troubleshooting and improving them as per the desired use case.

Infrastructure (bottom layer)

At the base, AI engineering relies on robust infrastructure to deploy and operate models.

This includes the serving stack (how you host the model and expose it), managing computational resources (typically means provisioning GPUs or other accelerators), and monitoring the system’s health and performance.

It also spans data storage and pipelines (for example, a vector database to store embeddings for retrieval), as well as observability tooling to track usage and detect issues like downtime or degraded output quality.

Based on the three layers and whatever we've learned so far, one key point is that many fundamentals of Ops have not changed even as we transition to using LLMs. Similar to any Ops lifecycle, we still need to solve real business problems, define success and performance metrics, monitor, iterate with feedback, and optimize for performance and cost.

However, on top of those fundamentals, AI engineering introduces new techniques and challenges unique to working with powerful pre-trained models.

Next, let’s take a look at some fundamental points that will help us understand what large language models (LLMs) really are.

LLM basics

Large language models (LLMs) are a type of AI model designed to understand and generate human-like text. They are essentially advanced predictors: given some input text (a “prompt”), an LLM produces a continuation of that text.

Under the hood, most state-of-the-art LLMs are built on the transformer architecture, a neural network design introduced in 2017 (“Attention Is All You Need”) that enables scaling to very high parameter counts and effective learning from sequential data like text.

Several characteristics and terminology related to LLMs:

Scale (the “large” in LLM)

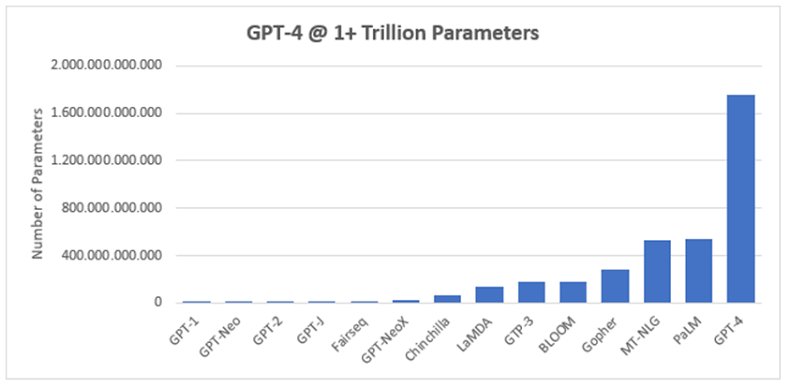

LLMs have a huge number of parameters (weight values in the neural network). This number can range from hundreds of billions to trillions.

There isn’t a strict threshold for what counts as “large”, but generally, it implies models with at least several billion parameters.

The term is relative and keeps evolving (each year’s “large” might be “medium” a couple of years later), but it contrasts these models with earlier “small” language models (like older RNN-based models or word embedding models with millions of parameters).

Training on massive text corpora

LLMs are trained in an unsupervised manner on very large text datasets, essentially everything from books, articles, websites (Common Crawl data), Wikipedia, forums, etc., up until a certain cut-off date.

The training objective is often to predict the next word in a sentence (more formally, next token, since text is tokenized into sub-word units). By learning to predict next tokens, these models learn grammar, facts, reasoning patterns, and even some world knowledge encoded in text.

The training process involves reading billions of sentences and adjusting weights to minimize prediction error. Through this, LLMs develop a statistical model of language that can be surprisingly adept at many tasks.

Generative and autoregressive

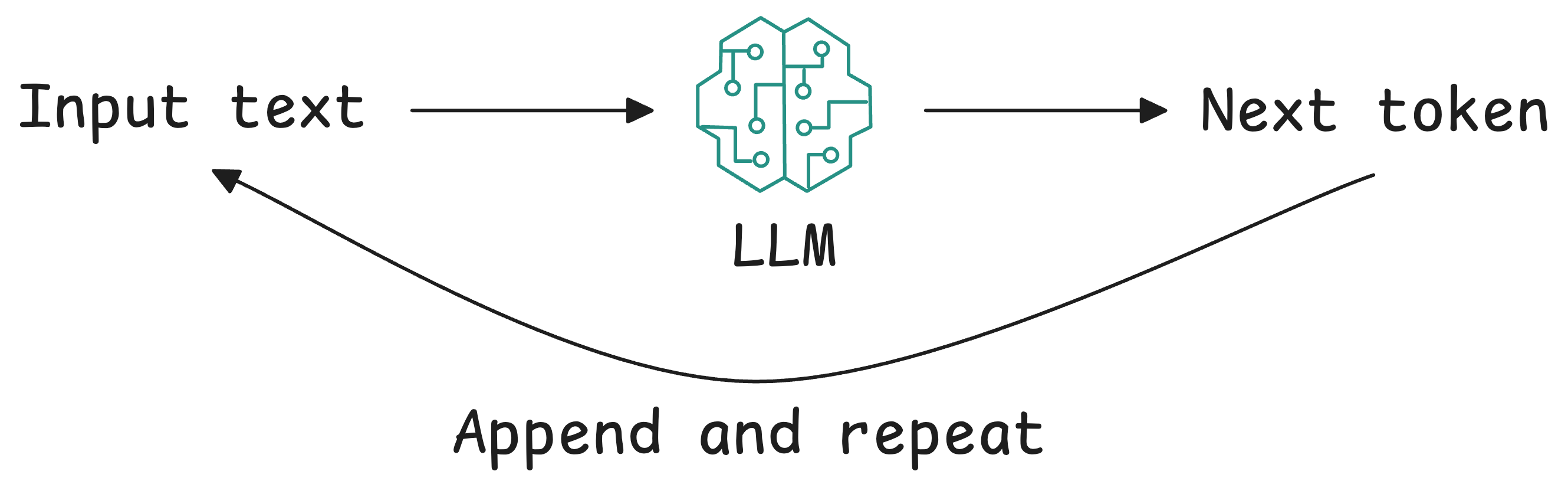

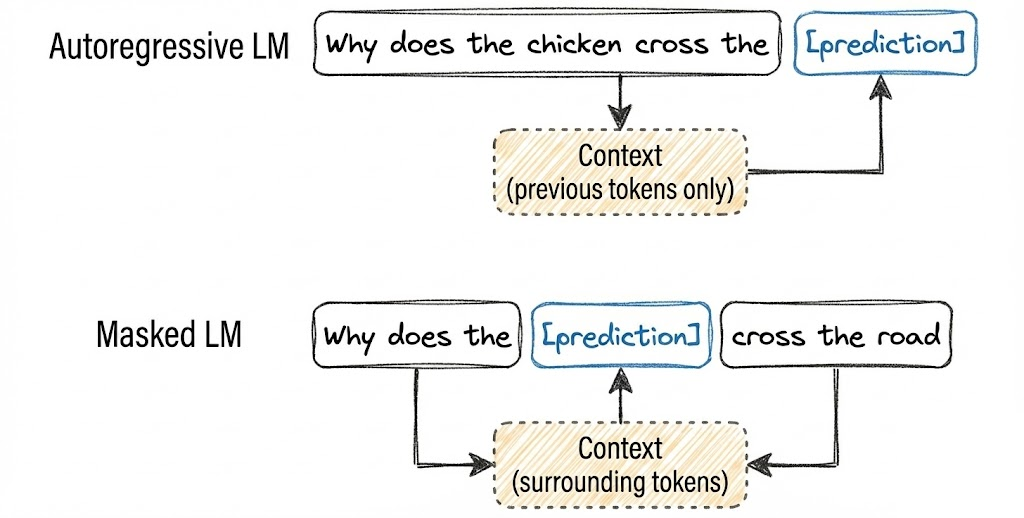

Most LLMs (like the GPT series) are autoregressive transformers, meaning they generate text one token at a time, each time considering the previous tokens (the prompt plus what they’ve generated so far) to predict the next.

This allows them to generate free-form text of arbitrary length. They can also be directed to produce specific formats (JSON, code, lists) via appropriate prompting. LLMs fall under the Generative AI category as well, since they create new content rather than just predicting a label or category.

Another kind of LMs is masked language models.

A masked language model predicts missing tokens anywhere in a sequence, using the context from both before and after the missing tokens. In essence, a masked language model is trained to be able to fill in the blank. A well-known example of a masked language model is bidirectional encoder representations from transformers, or BERT.

Masked language models are commonly used for non-generative tasks such as sentiment analysis. They are also useful for tasks requiring an understanding of the overall context, like code debugging, where a model needs to understand both the preceding and following code to identify errors.

Emergent abilities

One intriguing aspect discovered is that as LMs get larger and are trained on more data, they start exhibiting emergent behavior, i.e., capabilities that smaller models did not have, seemingly appearing at a certain scale.

For example, the ability to do multi-step arithmetic, logical reasoning in chain-of-thought, or follow certain complex instructions often only becomes reliable in the larger models.

These emergent abilities are a major reason why LLMs took the world by storm. At a certain size and training breadth, the model is not just a mimic of text, but can perform non-trivial reasoning and problem-solving. It’s still a statistical machine, but it effectively learned algorithms from data.

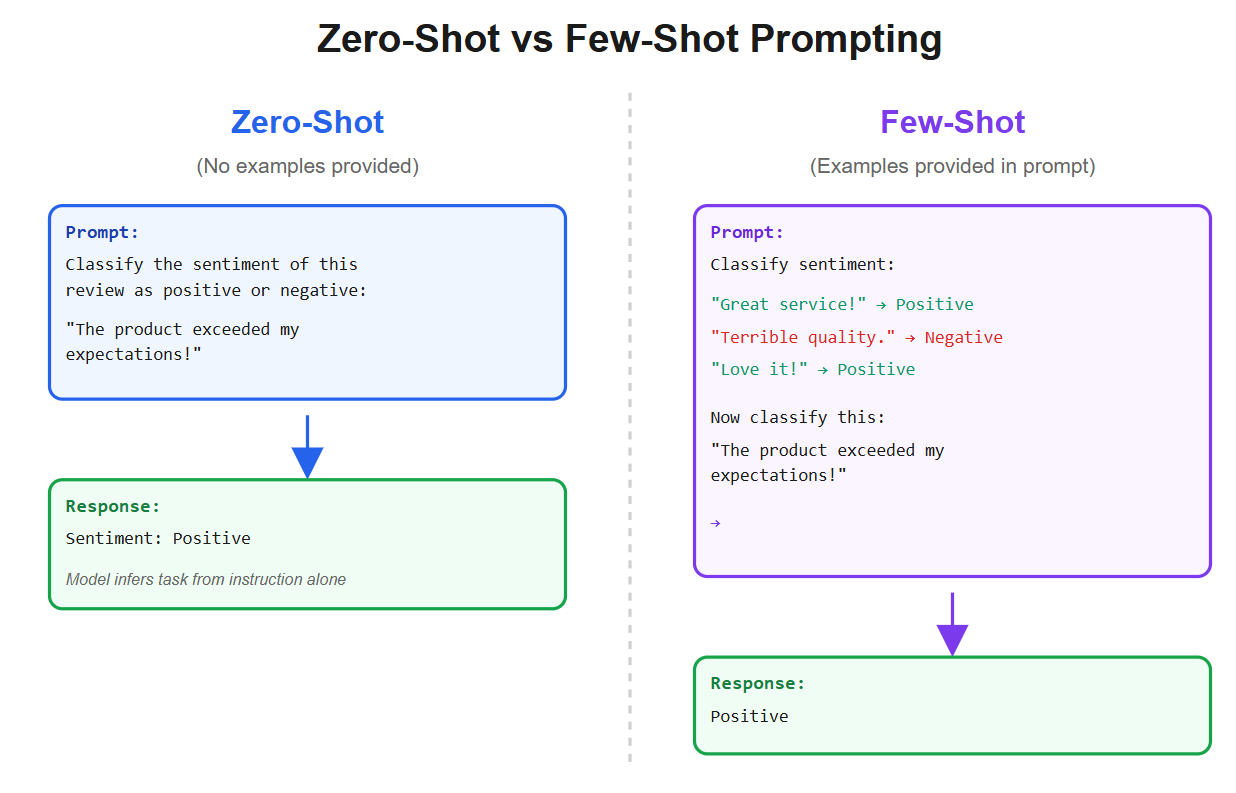

Few-shot and zero-shot learning

Before LLMs, if you wanted a model to do something like summarization, you’d train it specifically for that. LLMs introduced the ability to do tasks zero-shot (no examples, just an instruction in plain language) or few-shot (provide a few examples in the prompt).

For instance, you can paste an article and say “TL;DR:” and the LLM will attempt a summary, even if it was never explicitly trained to summarize, because it has seen enough text to infer what “TL;DR” means and how summaries look.

This was a revolutionary shift in how we interact with models: we don’t always need a dedicated model per task; one sufficiently large model can handle myriad tasks given the right prompt.

This is why prompt engineering became important; the model already has the capability, we just have to prompt it correctly to activate that capability.

Transformers and attention

For a bit of the technical underpinnings, transformers use a mechanism called self-attention, which allows the model to weigh the relevance of different words in the input relative to each other when producing an output.

This means the model can capture long-range dependencies in language (e.g., understanding a pronoun reference that was several sentences back, or the theme of a paragraph).

Transformers also lend themselves to parallel computation, which made it feasible to train extremely large models using modern computing (GPUs/TPUs). This architecture replaced older recurrent neural network approaches that couldn’t scale as well.

Limitations

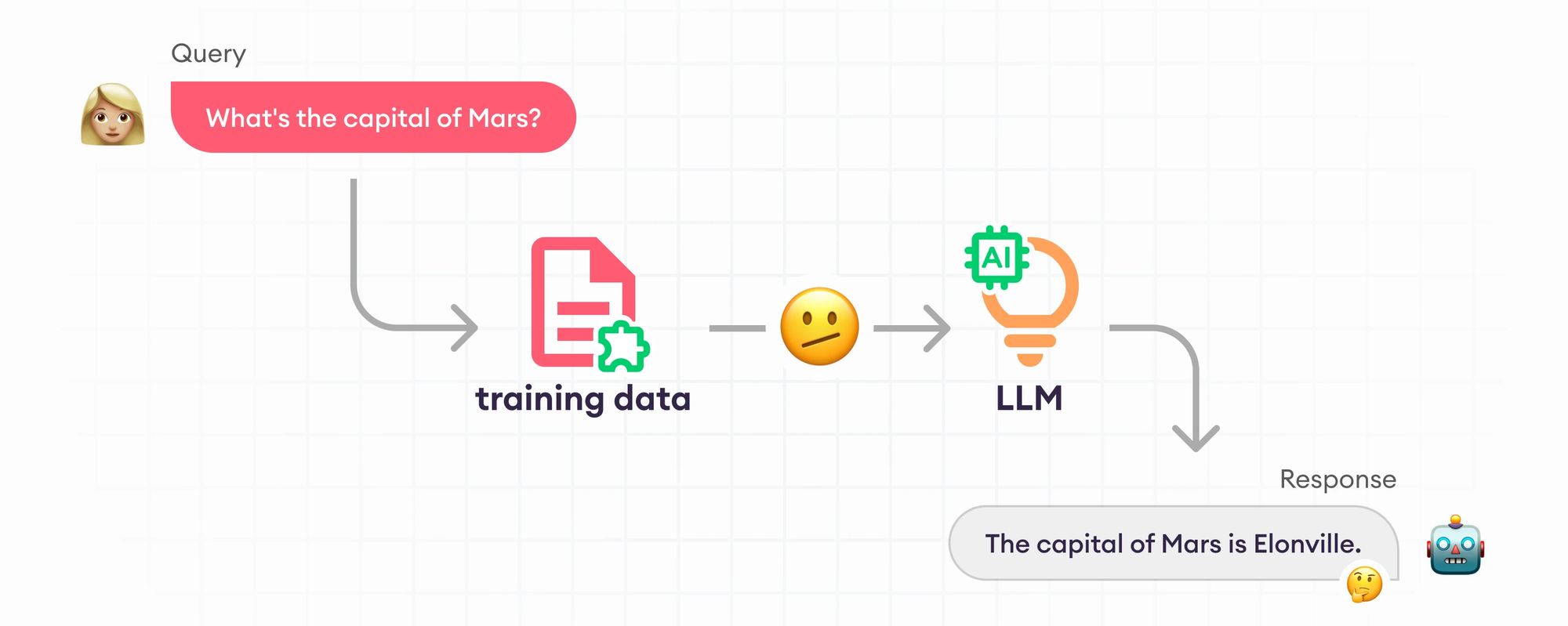

It’s important to remember LLMs don’t truly “understand” in a human sense. They predict text based on patterns, i.e., basically, they are probabilistic. This means they can be right for the wrong reasons and wrong with high confidence.

For example, an LLM might generate a very coherent-sounding but completely made-up answer to a factual question (hallucination). They have no inherent truth-checking mechanism; that’s why providing context or integrating tools is often needed for high-stakes applications.

It’s also worth noting that making a model larger yields diminishing returns at some point. The jump from 100M to 10B parameters yields a bigger improvement than the jump from 10B to 50B, for example.

So just because an LLM is extremely large doesn’t always mean it’s the best choice. There might be sweet spots in the size vs performance vs cost trade-off. Engineers often choose the smallest model that achieves the needed performance to keep latency/cost down.

For instance, if a 7B model can do a task with 95% success and a 70B model can do it with 97%, one might stick with 7B for production due to the huge difference in resource requirements, unless that extra 2% is mission-critical.

In summary, an LLM is like an extremely knowledgeable but somewhat alien being: it has read a lot and can produce answers on almost anything, often writing more fluently than a human, but it might not always be reliable or know its own gaps. It’s our job to coax the best out of it with instructions and context, and curtail its weaknesses with evaluations.

The shift from traditional ML models to foundation model engineering

Traditionally, deploying an AI solution usually means developing a bespoke ML model for the task: gathering a labeled dataset, training a model, and integrating it into an application.

This “classical” ML engineering was very model-centric; you’d often start from scratch or from a small pre-trained base, forming the data → model → product flow.